In this second installment of How Games Tell Tales, I will discuss a particular aspect of video games: simulation. By using some theories on historical simulation, I will use Nioh as an example of how games can represent history and mythology.

Spoiler Warning: This article discusses both Nioh titles, with mild spoilers for both. They follow Japanese history and folklore though, so there might not be many surprises if you are in any way familiar with that.

In the first iteration of this series of articles, posted a week or so ago, I explored how The Last of Us is an example of games telling stories through the act of player control. Today, I will explore one of the ways in which games represent worlds, especially that of history: simulation.

As such, the second game(s) in this series will be the Nioh franchise, a series of two games that were released in 2017 and 2020. The story of these action-role playing games takes place around the year 1600 in Japan, referred to as part of the Sengoku period. They mix folklore, mythology and history, in a relatively unique blend. In this article, I will focus on a few ways in which these games simulate history, by explaining parts of simulation theory, and applying it to the narrative of this series.

Games as Historical Simulation

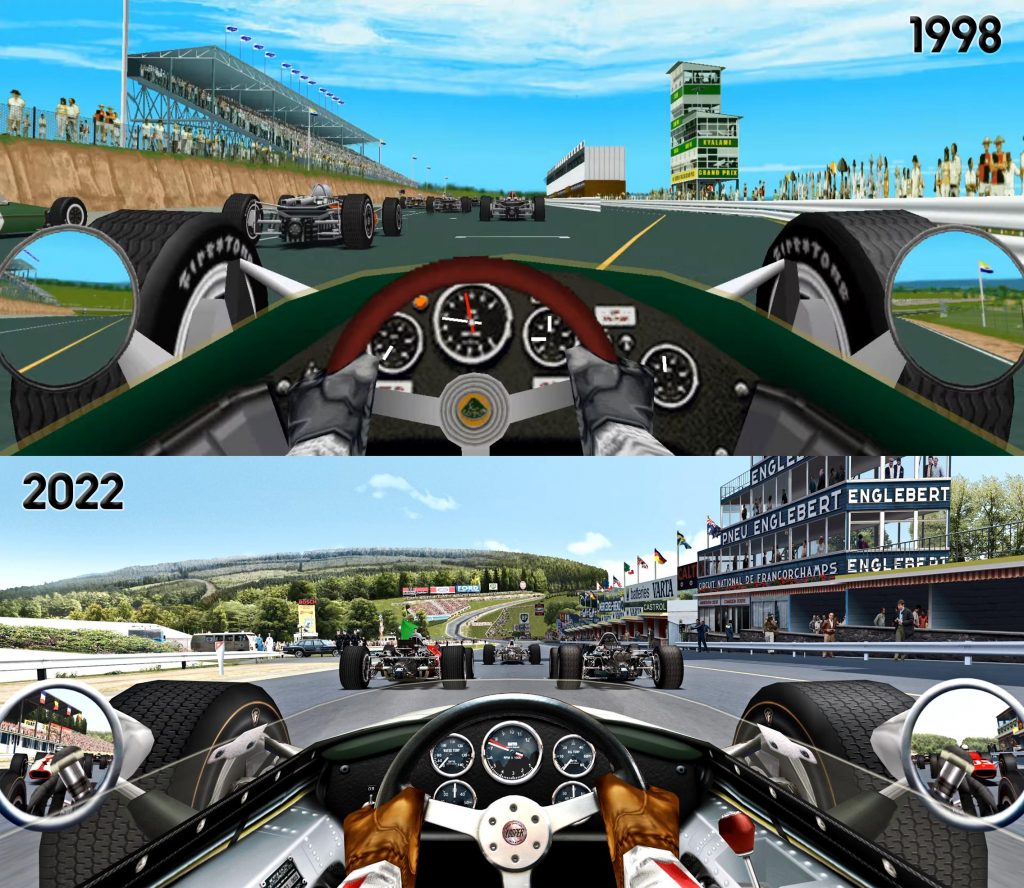

One of the first writers on historical simulation in video games was William Uricchio. He wrote about Grand Prix Legends, a racing game that portrays the Grand Prix of 1967. The game presented this Grand Prix along with a first-person perspective of a driver, simulating what it would be like to drive a formula 1 car in 1967. Uricchio refers to this as a specific historical simulation, representing a specific time in history. For non-specific historical simulation, Uricchio refers to Civilization, in which you can play any historical leader in any represented time, as you play as Norsemen with submarines. Another game that would fit this is Skyrim, which simulates an idea of history, like castles and emperors, in a non-specific fantasy setting. Of course, these two games simulate history differently: Civilization plays with actual history, while Skyrim places historical elements in fantasy.

Nioh quite clearly falls under the category of specific historical simulation, as it represents Japan during the Sengoku period, with samurai, feudal lords, battles (and a lot of references to drinking tea). However, it also toys with the reality of its simulation. The Nioh games add yōkai to the simulation, spiritual beings of folklore. They also allow the player to be a character that is shown to be present within the history that is simulated. Finally, they choose what version of history to present as having happened, and thus influence what players remember of the history they are being shown. These few ways in which Nioh simulates history interestingly will be explored further in the rest of this post.

Introducing Yōkai: Mixing Myth and History

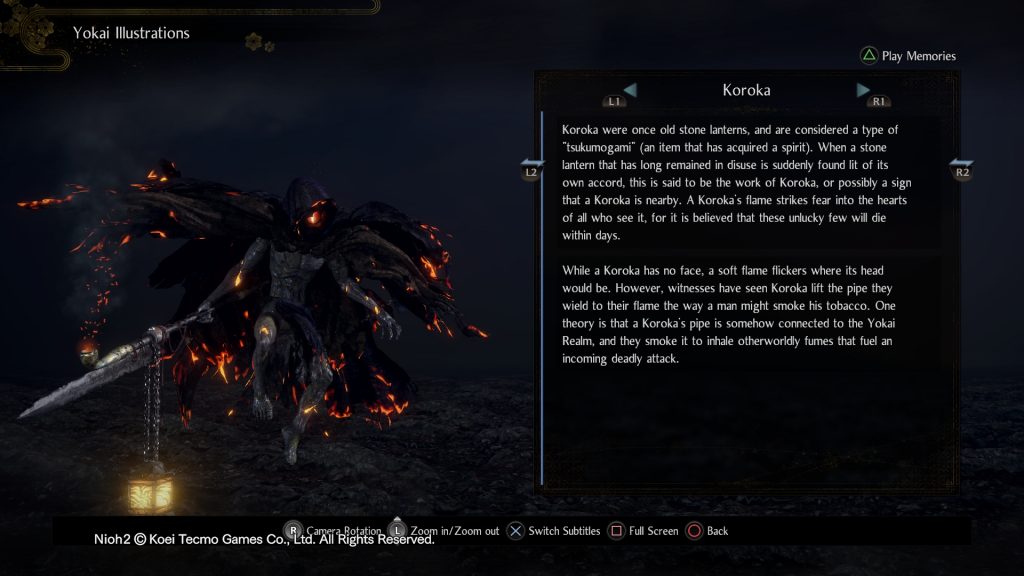

What are yōkai? A book would not even give a full answer, to be honest, but the short of it is: Spiritual beings, demons, ghosts, good or bad spirits, etc. They can exist in humanoid form, or as possessed materials. And, most importantly, they are an important part of Japanese folklore and mythology.

Nioh mixes this folklore with the history it represents. Battlefields will be swarmed by these creatures, as you collect tree spirits named Kodama. All major historical characters are presented as having guardian spirits, whose powers help them and you. Some characters from history even turn into yōkai themselves.

So what does this do with the historical simulation? It is not, per se, history as it happened in the books, right? Well, it infuses history with culture. After all, folklore is part of history too. The Olympians are as much a part of Greek history as their battles were, we still visit their temples or see their statues in museums. This addition of folklore allows for the developers to quite literally play with history. In the first game, one of the characters states he will never mention that any yōkai were present, playfully explaining why it is not present in the history books.

In a sense, adding this folklore and mythology makes the simulation more playful, but also more culturally relevant and historically rich. The Nioh games do not just dryly simulate a narrative of history, they also supply a narrative of Japanese cultural folklore and myth. In a similar way that Arthurian tales play a role in the history of Western Europe, these myths play a role in the history of Japan, and the games simulate this quite literally.

This simulation of history and folklore does not end with just other characters, the player is part of this just as much as the protagonist.

Protagonist Problems

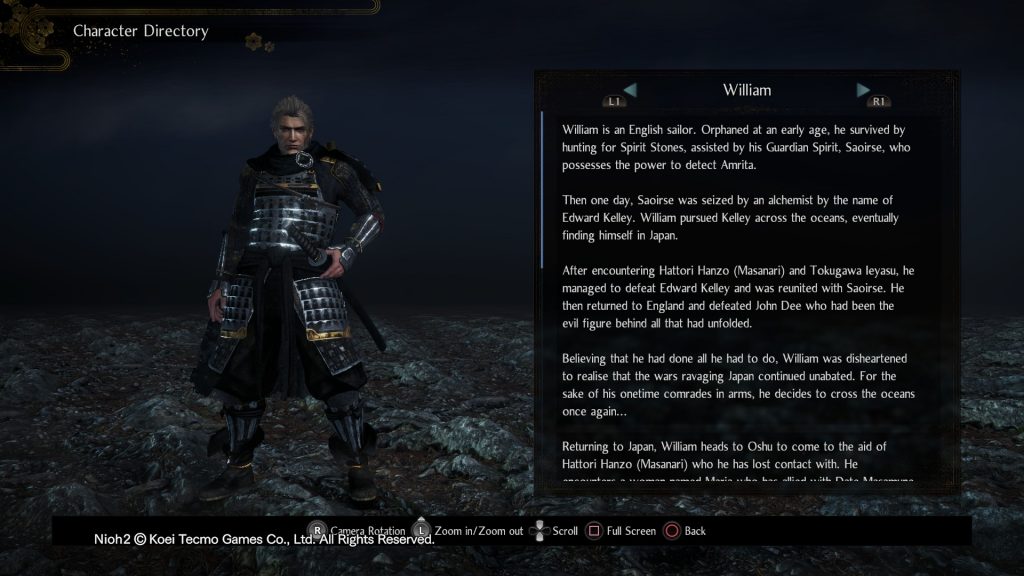

When simulating history for a game, how do you let a player interact with it? That can be a tough question to answer, and the Nioh games have found an interesting way to answer it. In the first game, you play as William Adams, a man who actually existed, and appears to have been one of the first western samurai. It is disputed how much of Japanese history William influenced, as it has been argued that there are two versions of the man: the historical one, who established trade connections, and the mythological one, who played a role in all of Japanese history while he lived. It is this mythological figure the player finds themselves playing as. In this simulation of history, you are as mythological as the yōkai you find yourself fighting.

In the second game, the player plays a hybrid between a human and a yōkai, called Hide. Through a partnership with a later leader of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, you explore a different perspective of Japanese history during roughly the same period. It is even suggested that your character is the reason for Toyotomi’s last name, as you have a partnership with the man, and are partly responsible for his accomplishments, so he takes on a combination of your name and his. Of course, alike with the yōkai before, this part of the story would not be told, and that is why it is not in history books.

By making the protagonists ahistorical, they can act like flies on the wall of historical events. They did not directly change the outcome of Japanese history, as they (likely, in the case of William) were not even there. This allows the simulation of history to unfold, the narrative to follow that of books and other sources, while the player can be amidst all of it. It is a clever way to not break the specific simulation of history that is presented, without making the player feel powerless. They did influence the story of the game through their battles, but it did not change history as we know it today.

Deciding the Facts of History

Now, what happens when the actual historical sources on an event are rather vague? How can you simulate history when you do not even think you know what happened? This is another question Nioh comes across, with the assassination of Oda Nobunaga. The event itself is quite clearly happened: Nobunaga was attacked at the temple of Honnō-Ji by Akechi Mitsuhide, one of his generals. Nobunaga died, committing seppuku. The burning of the temple is shown in the second game, and is featured as the banner to this post.

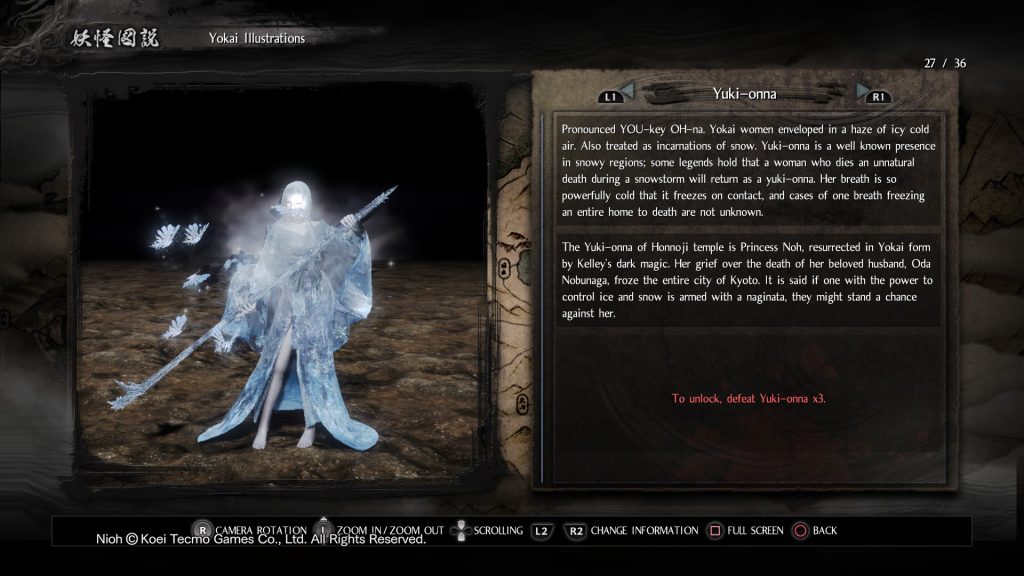

The first Nioh game deals with the aftermath of Honnō-Ji, with the player fighting a snow woman yōkai, a yuki-onna. It is sort of hinted that this is Nobunaga’s wife, whose fate at Honnō-Ji is unknown, as she either died or escaped. The game, thus, suggests she might have died, and that she was turned into a yōkai, at least partially from grief.

Another part that is unknown is why Mitsuhide did this act. There are theories, of course. Jealousy, a desire for more power, plotting with Toyotomi Hideyoshi…wait a minute, Hideyoshi is in the second game!

In this second game, the plot suggests that Hideyoshi conspired to kill Nobunaga. He would do so through Saito Toshimitsu, who is trusted by Mitsuhide. Toshimitsu convinces the latter that Nobunaga is corrupted, which is why Mitsuhide would perform the attack. After this, Hideyoshi waged war with Mitsuhide’s forces, and took control of Japan. Essentially, the game presents a plot by Hideyoshi to take control, using Mitsuhide.

What we see here is interesting. The game is deciding how history went. While the assassination attempt is rather well documented, the reasons for the assassination, and the fate of Nobunaga’s wife, are entirely uncertain. The game’s developers have decided to simulate their own version of events, to pick a truth out of history, and to tell their own narrative. The choice to not represent ambiguity, but rather present a single version of history is interesting. This does not have to be a bad thing. However, it might still make players believe a specific truth of history, whereas history is more ambiguous than it is presented as. The game’s developers have chosen to reflect a certain theory of history as a truth, and it is important to note that this influencer’s players and their possible perception of history, even with the fantastical additions of mythology and folklore. All of this mostly shows what I said about history in my first post here: history is a story we tell each other, and simulations of it are not immune to this – they still simulate a chosen version of events.

P.S. Of course, these are but a few aspects of historical simulation. Architecture, for example, was not discussed here, as it is not something I am specialised in. Uricchio is far from the only writer in this field, and his theory is not the end all be all to historical specificity either. Simulation theory is broad, and so is historical simulation theory. It is, however, important to bring it up, even if relatively simplified, since talking about historical games inherently talks about how they simulate matters.