With Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla just around the corner, Liam McLeod talks about historical accuracy in the game. But aside from pointing out what Valhalla got right and wrong, there is a lot more to unpack. How does Valhalla repeat nationalistic narratives? And should developers take more care with their histories? Liam touches upon all that below!

How important is ‘historical accuracy’?

This topic so often arises when discussing historical games, but particularly so it seems when Ubisoft becomes involved. It’s been nearly two months since Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla slid onto the stage with a trailer which raised some eyebrows from historians and fans alike. The new game is set in early medieval England during Alfred’s the Great’s reign, which places the game world towards the end of the ninth century.

As a researcher of early medieval Europe, I was a little surprised by some of the trailer. Whilst the architecture for the Scandinavian communities seems in keeping with what you might expect, Alfred’s castle(?) in which he narrates the trailer seems more reminiscent of a post-Norman setup than a ninth-century English one… Some of the Viking armour also appears to be a little dubious – I support the choice to not include horned helmets, but I’m not sure how the odd bit of pelt and fur would keep you safe from the most ludicrous two-handed sword in Western Europe.

The helmet this beast of a man wears also appears to be a strange blend of the red-crested Roman galea and the helm found at Sutton Hoo, an archaeological site which yielded some of the most important finds from sixth- and seventh-century England:

Historical accuracy is a moving dartboard though, and while it’s sometimes easy to say what is off the mark in a particular depiction of the past, it’s often less easy to say definitively what is right. Historians and archaeologists alike are ever imagining and re-imagining the past as new evidence and methodologies arise. The past isn’t a static truism. Rather, it’s more like viewing the outside world through a frosted window: the shapes of figures dancing in the snow can be seen, but we’re not part of that world and we don’t always understand the rhythm of the beat. Should we be so quick to jump on developers then to uphold our subjective perspective on ‘accuracy’? Probably not. In some ways, it’s comparable to holding Bram Stoker accountable for not portraying a historically accurate account of aristocratic life in Transylvania; it was never the goal of the novel, and it doesn’t have to be the goal of video game developers either. For Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed IP, however, this is a little different. Assassin’s Creed has been built and marketed on the idea of presenting rigorously researched game worlds which are reflective of historical cities and environments. For Valhalla, according to the game’s narrative director Darby McDevitt, this is apparently no different:

Very few games actually treat the Norse Viking experience as historically grounded. I think the urge is to always immediately lead with the mythology stuff, but we really want you to feel like you’re living in the Dark Ages of England, that you’re exploring the Roman ruins left behind 400 to 500 years earlier by the Romans and the remnants of the Britannic tribes before that and even the Saxon Pagans before they all converted to Christianity.

If Ubisoft is presenting this decidedly wide of the mark historical space as unerring then what might this mean for its narrative direction and the impact on the player? Misconceptions and inaccuracies of the past have a way of being interpreted to suit modern narratives. Magna Carta, for instance, has often been used by British politicians to demonstrate a particular image of a civilised and humanitarian English culture since time immemorial. This is despite the original document being less (if at all) interested in civil liberties and instead being far more concerned with solidifying aristocratic power; for the few and not the many, indeed. The crusades too were employed by George Bush at the inception of his ‘crusade on terror’, implicitly endorsing age-old Western ideas of a valiant and noble crusader against the tyranny of evil powers. The problem here is that it so effortlessly constructs a black-and-white world view, one which positions the Middle East as the source of an ancient evil risen again, and the West as a bastion of hope and moral infallibility. In short: it ignores the modern political environment and instead favours well-trodden archetypes that position Western powers as noble and blameless, free of the evils in which Islamist terrorists are entrenched. It positions different cultures and peoples as ‘the Other’ in order to service narratives which lionise America and its allies.

Video games are in an especially dangerous position in this respect. They often draw on power fantasies which cast aside the complexities of the real world to achieve the entertainment value of the product. Developers therefore must be careful to not produce (and endorse) the one-dimensional narratives to which their source material can so easily lend itself. It’s not only the responsibility of developers, however, to keep a watchful eye on the historical narratives of their virtual worlds… Players and scholars alike must be ready to approach the narratives of the game world as they would with any other media: critically. It’s easy to be pulled into a state of immersion in high quality virtual worlds. Placing you in the driver’s seat, video games incorporate players into the narrative in a way that is unique across entertainment media. This participatory experience often predisposes players towards accepting the stories presented to them at face value, even if they might be reductive, one-sided or dangerous.

Nationalist Narratives and AC: Valhalla.

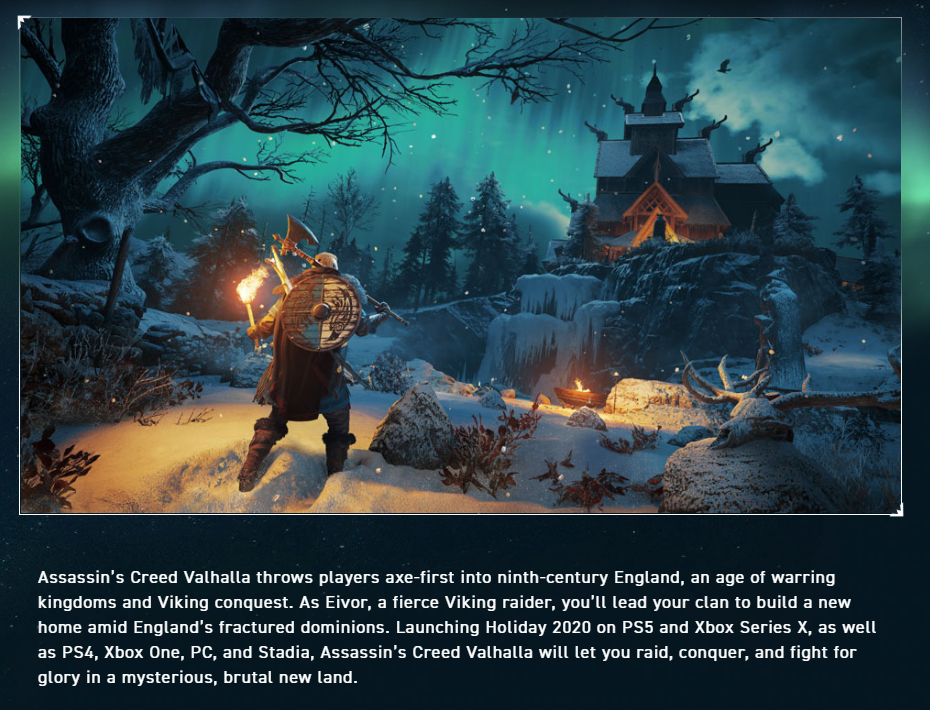

Let’s re-examine that first image I’ve presented here. Aurora Borealis shimmering in the sky of a dark and cold place, decidedly Scandinavian architecture, and the scent of destiny exuding from our hero as he looks into the distance. Whilst the image itself is stunning, it’s the caption that is perhaps most interesting for considering the narrative the developers want to tell us:

Assassin’s Creed Valhalla throws players axe-first into ninth-century England, an age of warring kingdoms and Viking conquest. As Eivor, a fierce Viking raider, you’ll lead your clan to build a new home amid England’s fractured dominions. […] Assassin’s Creed Valhalla will let you raid, conquer, and fight for glory in a mysterious, brutal new land.

Valhalla is leaning heavily into this ‘dark age’ idea of the Middle Ages, a period where there is only war, death, and ‘brutal […] land[s]’. From the perspective of a historian of this period, it’s fascinating to see how far-reaching this ‘dark age’ trope still is. There’s no mention here of the cultural renaissance of writing or intellectualism that – for me – dominates this period. When I speak to students about my period or present my research in academic fora, the thing I find myself constantly reiterating is how stunningly sophisticated this age is – and how varied its communities are. A good example of this might be the eighth-century Bonifatian mission to Germany, where English scholars began developing and standardising the groundwork for the future Carolingian Church. Their letters are awash with hidden references to profound Christological concepts, hinting at the metaphors and identities which these communities so often had to tackle with in the early medieval Church. Alfred himself was involved in an education campaign designed to translate biblical writings into Old English, beginning a transitionary education towards a Latin-proficient population. Women authors put pen to page throughout the eighth-century, and scholars such as Lynda Coon and Felice Lifshitz have commented extensively on the significant impact women had on their intellectual and political environs. Lifshitz in particular has demonstrated the quiet rebellion of English scholars in Francia, who removed misogynistic clauses from key legislature before forwarding them on. In effect, this seems to have reduced the curtailing of female agency in Frankish border territories and safeguarded women’s contributions to ecclesiastical intellectual culture (for a time at least).

What is the effect of this flattening of the period into one of only war and carnage? The temptation might be for some players to shrug this off; they might argue that it is a necessary part of making a combat-focused game world. There can’t be constant battle if there isn’t an ever-raging war, right? Well here’s where Valhalla takes a dark turn… This primal England that Ubisoft presents, speaks to some concerning ideas surrounding nation-building and nationalism. On Ubisoft’s website they refer to the Heptarchy – the seven kingdoms which once ruled the region we now call England – when they speak of the ‘broken kingdoms of England’. The implication here is that these regions would inevitably make up the country that we know today, and that this raw England sits at the core of its creation, just ready to leap into the foreground. If historians hadn’t already burnt out our sweat-glands from the anxiety of our PhDs, then this would set most of us into spiralling panic. The Heptarchy was never fated to be the land we know today, and the narrative that it was sets a disturbing precedent for the inevitability of England: ‘England’ becomes a monolith in time, permanent and static. These ideas are implicit in extremist notions of nation-building.

Modern regimes that have leaned towards nationalist extremes have often used the falsehood of historical staticity to strengthen nationalist bonds. For the Nazis, this was enacted through the unearthing of false artifacts. By showing the German public archaeological findings which solidified the connection between modern Germany and Teutonic peoples, Hitler and Himmler sought to demonstrate the power of an Aryan race throughout time. This saw an adaption of fringe theories, like those of Gustaf Kossinna, take on a new primacy in the German state. Kossinna had argued for the annexation of modern Poland by Germany in the wake of the Treaty of Versailles due to the ‘German’ archaeological finds that had been made in the region. Kossinna’s view – as expressed in a 1919 publication – went on to be used by the Nazis to justify their claims to Poland: they were simply reclaiming it from barbarians who had wrongly taken it from their ancestors.

These ideas surrounding the construction of nations and their heritages seem to have silently slipped into the perspectives which shape Valhalla too… In an interview with Theirry Noël, the resident historian working with Valhalla’s team, a lot of these disconcerting themes come into the foreground as Noël tries to unpack the setting for players:

It’s a fascinating time. It’s been called the Dark Ages because we don’t have as much information relative to certain time periods like Ancient Egypt or Greece. It may be dark, but it’s also a period of transition and transformation. The Roman world has disappeared, and the medieval era has not yet totally arrived. It’s a really interesting period of rebuilding the western world, rebuilding values, rebuilding states and nations […]

This notion of Rome’s fall was popular at one time of day, and authors like Edward Gibbon were keen to jump on this in the 18th-century as it spoke to the colonial, imperial ideals of the day. (Gibbon, for instance, blamed the ‘fall’ on everything from homosexuals to moral corruption, to Christianity. A good video on Gibbon and his role in modern historiography can be found here.) Today, however, most scholars have moved away from this perspective, least of all because it reduces subsequent kingdoms to pale shadows of a Roman ideal and glosses over the existence of Byzantium, who continued to self-define as ‘Romans’ well into the 15th century. This notion of ‘rebuilding the western world’ should also be a point of concern for us as informed players… The ‘western world’ as we so readily know it today is a product of imperialism and colonial states which emerged throughout much of the last five centuries, and while the relationships between kingdoms in Western Europe may have been deeply impactful for all involved, it’s anachronistic and short-sighted to impose our modern ideas of The West™ on the people of the early Middle Ages.

Nationalism-come-White-Supremacy: Virtue in Violence.

In the reductive environments of nationalism and ‘total war’, it’s not unusual for us to see white supremacy rear its head too. Liberal social values are often portrayed across various media as incompatible with brutal fictional landscapes. A name has developed for this phenomenon: ‘Grim Dark’. It’s a genre of fiction in gaming and literature in particular which proposes that in the direst of worlds, basic compassion simply breaks down. To players and readers of the Warhammer universes (be it Fantasy or Warhammer: 40k) this theme is all too familiar. Who has time to worry about socialised healthcare, after all, when three million orks are dropping from the sky in asteroids (‘Roks’) with the express intent of murdering you and everyone you know for the sheer thrill of it? The problem here is that for fascists and white-supremacists, these worlds are especially appealing because they offer free license to disregard the humanity of their fellow humans. They are worldscapes where brutality is inevitable, and kindness is a slippery slope to damnation and death. In essence, these worlds provide simpler lives to those unwilling to recognise the complexity of human civilisation and its shortcomings.

The iconographies of these worlds are not new, however. While we may want to have some stern words with Games Workshop about the communities that can so easily thrive in their fictions, this supremacist-coated brutality did not start with a London-based games company in 1975. As futuristic as GW’s 40k franchise may look, it’s ultimately rooted firmly in public perceptions of the medieval: a grim, hopeless, ‘dark’ age…

Valhalla’s ‘dark age’ of ‘broken kingdoms’ provide a similar environment to the world of Warhammer 40k, but perhaps more disconcertingly they also toy with images and symbols which have so often been the domain of white-supremacists. Dr Dorothy Kim, professor of medieval literature at Brandeis University, perhaps puts the association between Vikings and white-supremacists most succinctly:

That the Viking characters of Valhalla should be portrayed as virtuous is therefore all the more disconcerting… In the trailer, our narrator (presumably Alfred) insists that the player character and his community ‘murder and kill blindly. They scar the lands of England, lands they will never defend, never love.’ All the while, images of the player character sparing women and children play across the screen. This notion of defending women and children is particularly worthy of note; it is a common call to arms for white-supremacists who often frame their ‘defence’ of hearth and home in tones of vulnerability, where women and children share a comparable ineptitude for self-defence and personal agency. These danger narratives are as much a reflection of concerns about national interests as they are any legitimate fear for women or children: if women and children are defenceless, then the supremacists simply must intervene tosave them.

The trailer goes on to show these virtuous Vikings as setting up permanent residences with families and children playing around them. In other circumstances this might serve as a good demonstration of how the Vikings of history were more complex than simply the monsters who murdered innocents in search of wealth and territory. However, when placed in the context of Ubisoft’s other public media for the game, it becomes somewhat chilling: they take on an almost untouchable status and are shown as virtuous regardless of the events of history. Far from offering a nuanced perspective on the Vikings of the ninth century, Ubisoft has constructed a culture which is beyond reproach and one which doubtless speaks to the simplified narratives of the alt-right.

The Future of Valhalla

Ultimately, we still haven’t seen a great deal of Valhalla, and Ubisoft doubtless intends to reveal more of the game before launch, anticipated some time in December of this year. Players and scholars alike should be wary of where this narrative goes and treat the game with some caution. Video games continue to become a growing and fascinating part of modern life. In the process of creating this content though, developers should both be careful about unintended baggage and resist the archetypes and tropes which, though familiar to their demographics, remain dangerous and rooted in nationalist, racist paradigms. Video games are as much a political beast as any other media, and creators must reflect on their practice: dangerous tropes need to be abandoned in order for the industry to build productively (and ethically) on their products.

Ultimately, historical accuracy should not be considered the metric for this entertainment medium. Reflecting on virtual game worlds and the stories they tell – historically grounded or otherwise – is key to building rich, nuanced, and vibrant narrative experiences, however. Ubisoft, like other developers, has a responsibility to its consumers to present narratives which defy the narrow perspectives of imperialism and white supremacy, not entrench them. When they fall short, we as consumers should feel able to hold these products to account and resist the visual language of supremacy and extremism.

Liam McLeod is a doctoral researcher in the College of Arts and Law at the University of Birmingham (UK). He specialises in Carolingian saints’ lives and the reception of Jerusalem in Frankish thought and writings. When he’s not thinking about saints you will usually find him with a controller in his hands or trying to put one in someone else’s! Liam can be found on Twitter @LiamMcLeod_e