In “Fan Studies Methodologies“, the 2020 special issue of Transformative Works and Cultures, I described how, as an autistic gamer, I engage with games in a different way, showcasing how (dis)abled gaming, neurotypicality, fannishness, and sociopolitical responses are never independent from one another. All the examples I named in that “autiethnography” were from my adult life, but looking back, these differences in engagement were already very noticeable when I was a kid. Therefore, in the following essay, I would like to recreate my small piece of the history of the mid ‘90s Dutch video gaming culture, which was a sort of “produser community” avant la lettre.

As a kid, I did not have many friends, but children from the neighbourhood did come to visit our house. I am not sure whether they liked me or just came over to watch movies on our Betamax, play on our 386 computer and eat the many different types of deep fried food my father would prepare for us. But in any case, with this varying group we played (with) computer games, often engaging in alternative ways of play. Sometimes that was rather simple, e.g. by the “battles”, which we did by playing a level from Ducktales (Disney Interactive Studios, 1990) or Commander Keen (Hall, 1990), writing down the points and then loading the game just before the level.

We also played with the games more indirectly. For example, as aspiring game journalists, we wrote our own “paratexts” (Švelch, 2020). We designed posters and made a kind of zine in PrintMaster (Unison World, 1987), with added advertising material of new games we saw in the toy shop, such as Sonic the Hedgehog (SEGA, 1991). Moreover, we also pretended to be game developers, who for example drew new levels for Commander Keen with our coloured pens and pencils. But whereas my brother, under the label of his own corporation Alcatraz, kept himself busy by designing his game – called “The Cowboys from Kansas” – from scratch, I was more involved in creating alternative versions of the games I loved.

Sometimes, my creative outlets were based in the game itself, for example, I made some new levels for Lemmings (DMA Design, 1991). But more often, I crafted wholly new versions of my favourite games, adapted to my wishes and skills. For, truth to be told, I was – and am! – a very lousy gamer. I am rather slow, have bad reflexes and often forget which keys to use for which actions. But what has always appealed to me in computer games are the musics and art work. For example in racing games, I had no intention of winning, I would throw the race to just enjoy the bleeps and the scenery. Also, I got very attached to my beloved in-game characters, making it even more upsetting if I would let them die. Especially when the Prince of Persia (Mechner, 1989) was killed in a guillotine trap, it was a horrific image for me.

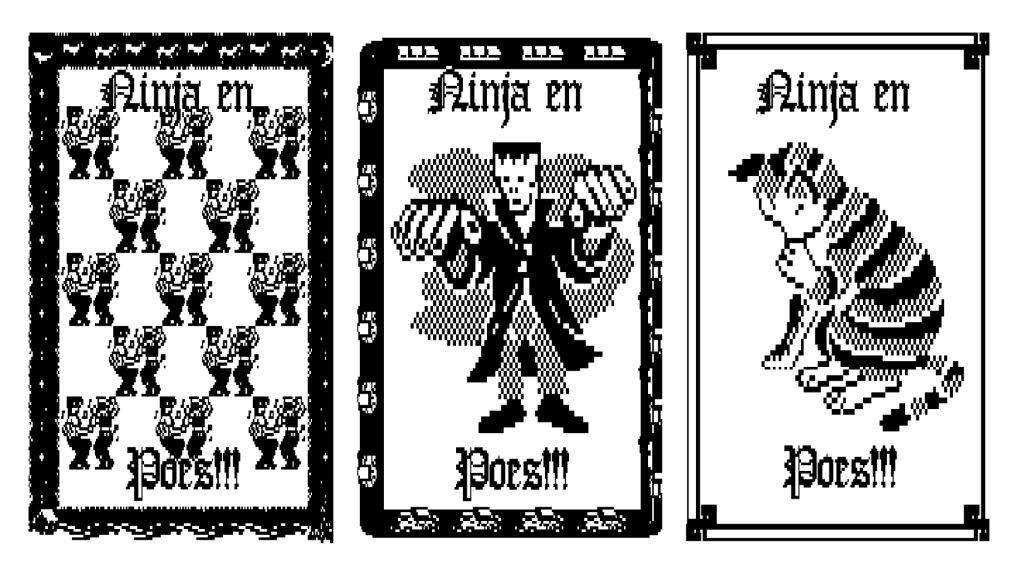

Therefore, I decided to create easier games for my beloved avatars. One of the programs I used in order to craft my own games was called “Klik & Play” (Clickteam, 1994). When the first levels were finished, I would copy them to 3,5 inch floppy disks to hand out to other kids. I also designed posters and flyers for the games in PrintMaster, often with neo-Victorian images (eg Frankenstein’s monster) and always with the protagonists’ names in my favourite neo-medieval font, in a childish form of nostalgia for the victorian era’s nostalgia for the Middle Ages. In this process, this group of kids basically became what Axel Bruns (2008) calls a “produser community”, in which users become produces of content, and usage and production are intertwined, so that the old distinctions between producers, distributors and consumers no longer apply.

All of the games and the poster designs are gone, now. They were on the old 386 pc that my father lent out to my aunt, so that my nephew could play on it. And when my aunt bought my nephew a newer machine, she just threw the old computer away, much to my regret. Also, no pictures of these homebrew games were taken, so the only images I have of them are in my head. But as I vividly remember what they looked like, I could do a reconstruction of some of the gameplay as well as the merchandise that came with it. In order to show and share this small piece of the history of early ‘90s Dutch video gaming culture, I ran DOSbox in order to play both Klik & Play (1994) and PrintMaster (1987) to recreate some of the images of that time. For this blog post, I have focused on two case studies, both from around 1994: Toy Cat, and Het Avontuur van Ninja en Poes (“The Adventure of Ninja and Cat”).

Case study 1 – Toy Cat (around 1994)

My first recreation is of my first Klik & Play creation: a game based on Alley Cat (Williams, 1983). I loved the level in which the cat must collect three ferns from the top of a bookshelf, but apart from the fact that it was super stressful to me when the spider appeared (I liked spiders, but this one did not like my avatar cat), reaching this level was a quest in itself, as it was hidden behind one of the windows you had to jump through. This was really difficult, as each window periodically opened to throw out random objects. Moreover, from the garbage bins came other cats that pushed you away, and there were also dogs running along the bottom edge of the screen.

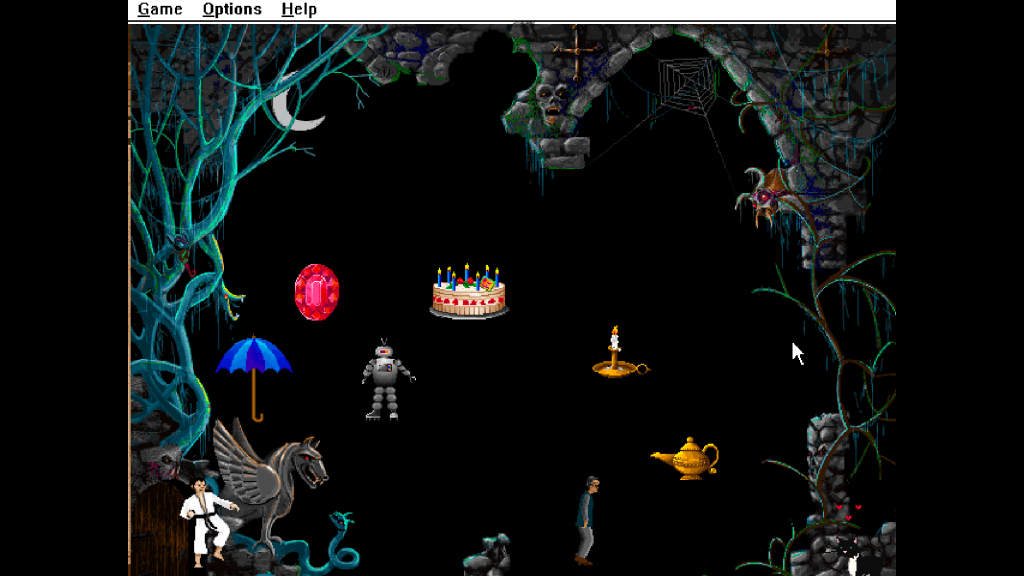

Long story short, Alley Cat was far too chaotic for my brain, even with the turbo button turned off. So, I decided to recreate my favourite level, without the spider, just the shelves and the cat. And this time, the cat could collect toys! As some kids had other computers at home, I also made versions of this game for the Macintosh. With my very limited knowledge of “porting”, that meant just redoing the whole game on the machine I wanted it to be playable on. Here is a screenshot from the reconstruction of the Mac version – ToyCat 2.0 – which postdates the original, in which the cat could collect all kinds of interesting Science Fiction toys (that were present in the Macintosh version of Klik & Play).

Case study 2: Het Avontuur van Ninja en Poes (around 1994)

“The Adventure of Ninja and Cat” was my attempt to rewrite the first Prince of Persia game (Mechner, 1989). The original game is set in ancient Persia, where a wizard locks the Sultan’s daughter in a tower. There she can choose: becoming his wife, or be killed within 60 minutes. Thus, the Prince must escape the dungeons, get to the palace tower, defeat the wizard and free the Princess, before time runs out. In addition to many hostile guards, the protagonist is further threatened by spike traps, deep pits, guillotines, a skeletal swordsman and even his own doppelgänger, conjured out of a magic mirror. The sword fighting in the game is rather advanced (consisting of maneuvers as advance, back off, slash, parry, and combinations thereof, like a parry-then-slash attack) and was therefore way beyond my skills. After some attempts to create additional – more easy – levels and mod the game with Princedit (Larionov, 1991), I decided to build a new game for the Prince, whom I called Ninja.

Instead of fighting guards in order to marry the Sultan’s daughter, in The Adventure, the protagonist – Ninja – would have to jump high to collect interesting things, as presents for Poes. Everytime the avatar touched an object, the object would disappear, and there would be hearts above Poes. The only danger was in touching Frankenstein (who was actually the monster of Dr Frankenstein, but I did not know that at the time). If Ninja would be too fast, he’d run into Frankenstein and would have to start all over with collecting the presents for Poes. Funny detail is that Poes would make a ‘mauw’ sound every time you got her a present. And once, my father came checking whether I had a real cat in the room with me – or at least, listening back to the Klik & Play audio, now, I think that this was a joke and what he pretented.

Nachleben

As I did not know how to include music – other than the occasional ‘mauw’ that Klik & Play could provide for – the games came with a cassette on which I had recorded some of the original game musics, some sounds from my cats purring and some improvisations of me singing new tunes for the new games in a made-up language. That way, if you would press ‘play’ as soon as the game loaded, you should experience a nice soundscape to play along with.

In order to spread the word about a new – and improved! – version of my beloved games, I often designed and printed some posters and flyers. I remember hanging the ones for The Adventure behind my window and waiting in anticipation of the people visiting our home to play this new game. I drew posters and made booklets by hand, but also used PrintMaster to print some posters. Here are some reconstructions of what these posters must have looked like, with images of Poes, Frankenstein and happy people – those were the people playing and liking the game, of course.

Sadly, my games were severely criticized by the other kids, most notably for the slow pace and the fact that “the levels were all the same”. I objected, for in Toy Cat you could collect different toy collections, but what they probably meant was that all objects were at the same locations on the screen. Their dissatisfaction with The Adventure was similarly, as that game only had different backgrounds, but the exact same game play. For me, it was a conscious decision to design my games in this way, as I like collecting things, and the repetition was a feature that I highly appreciated, for it made it easier to play and I like it when I know what to expect. Also, the other kids did not like the cassette with game music as they found it “weird”. Pity.

It became clear to me that these other people had a vastly different taste in gaming. Still, I enjoy the happy memories of the hours I spend crafting the new games for them. And with my recreation of two of these games, I hope to have added to the understanding of the intersections between gaming and autism, as well as to the history of the mid ‘90s Dutch video gaming culture, which was a sort of produser community avant la lettre.

Moreover, some interesting questions also arose from writing this small autiethnographic memoir. In the act itself, like how writing memories can serve as a locus of control for constructing a cultural identity. But also about the social life of play things and the authenticity of replicas. One thing that particularly puzzled me was the apparent shift in how the player relates to their avatar. For me, Poes and Ninja felt like my friends. Many psychologists have stressed that avatars can function as role models, but for me it was the other way around. I chose my avatars quite consistently, as fictive companions to the imaginary player I created out of myself.

Martine Mussies is a Ph.D. candidate at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and a professional musician. Her other interests include autism, (neuro)psychology, Japanese martial arts, video games, King Alfred, and science fiction. More: martinemussies.nl