While video games are a unique narrative medium, they have plenty in common with media like movies and books. So much in common, in fact, that they can tell the same stories, in a style of storytelling that is referred to as transmedia. But what is transmedia storytelling?

As stated in my introduction post just over a week ago, I want to explore how video games tell stories. I mentioned that games are a unique medium, one which creates narratives in a way other forms of media cannot. But before we can delve into the ways in which video games set themselves apart from the likes of movies and books, we need to realise that these media also have plenty in common. They can even share characters, or narrative universes, in a style of storytelling that is referred to as transmedia.

In this post, I will provide an overview of what transmedia storytelling is. I will then explore the role that video games have come to play within transmedia narratives, and how this style of storytelling is related to history as well.

What is transmedia storytelling?

Henry Jenkins first coined the term transmedia storytelling in 2003, and has expanded upon it in writing, lectures, and on his personal website. While the term is rather complex in these works, the basic notion is as follows: transmedia storytelling occurs when a narrative uses multiple platforms and forms of media to tell its story, in order to enhance the audience’s experience with the work.

Jenkins distinguishes between adaptations and extensions, with the first merely presenting the same story in a different medium, like turning a book into a movie. Extensions, meanwhile, add new dimensions to a story, such as new character traits or new perspectives on a world. This is a rather vague definition, and almost purposefully so. If you were thinking that an adaptation can also do these things, you would be correct. It’s a spectrum, some works adapt more than anything else, some extend, and others do both. This spectrum is useful to show how different media interact with the same stories, do they tell the same tales, or do they add to the narrative experience?

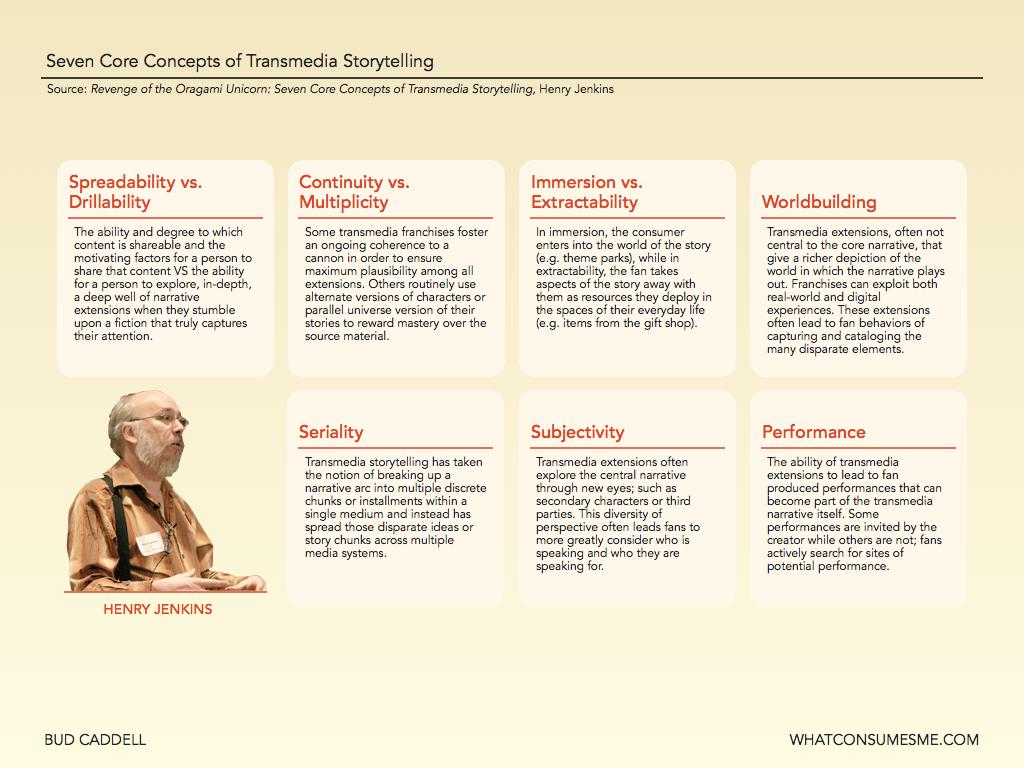

Jenkins thinks that there are seven core principles of transmedia storytelling, as seen in the image below.

That’s a lot. Fortunately, my post will not talk about all seven, it would be far too long if it even did. Some of these principles function as narrative building blocks, others are about audience interaction. They’re all interesting, but don’t exactly tell us how games (directly) differ from other media. I might write future posts about some of these left-out aspects such as ‘Performance’ and ‘Drillability’, as they are interesting for games as a whole. Immersion will almost certainly make a return in my next (shorter) post, so you can look forward to that! If you want to learn more about all seven of these principles, this article is a good place to start.

For this post, continuity and multiplicity are the most interesting. Do games continue a canon along with other media, like Jenkins’ prime example of The Matrix? Or do they present characters from other media in a new multiverse of sorts? Has their relation to other media changed from this perspective? The principles, along with the distinction between adaptation and extension, were thus coined by Jenkins in the 2000s. This might not seem like such a long time ago, but in 2003, when Jenkins wrote about transmedia for the first time, the franchise of Call of Duty was just about to start, and in 2009, when Jenkins posted about the seven principles, it was still the era of the Playstation 3. It is safe to say the game industry has changed and developed, so let us delve into what we see there these days!

Mythologies and Superheroes: Popular Adaptations

There is actually something else about the year 2009: It was the year that the Batman: Arkham series began. The reception of Arkham Asylum was excessively positive; it still has a 91 rating on Metacritic at the time of writing this post. Jenkins used Marvel and DC comics as examples quite often, noting that they wrote stories with continuity, but also ones with multiplicity. Arkham Asylum is a game that one can see as multiplicity, it presents a different Batman scenario and world than is seen in the movies of that era, and tells its own story in that universe. Of course, superhero games were not new, but Arkham Asylum marked a change in their popularity. This popularity was clear when the 2018 Spider-Man game – featured as the banner to this post – broke sales records for Sony at its launch. It is safe to say that the superhero genre is a transmedia narrative at its core, but Spider-Man even moreso. One can take the character of Peter Parker, and put him in new situations, new universes, and new scenarios, and still have a sense of continuity. As the Into The Spider-Verse movie states: anyone can be behind the mask.

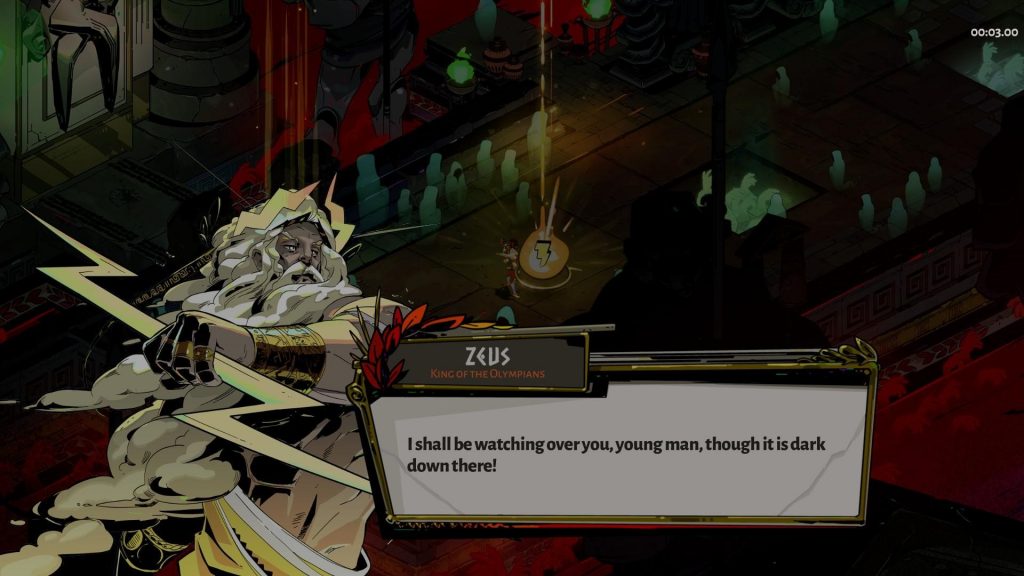

It is not just superheroes that have seen a surge in video game adaptations: mythology is adapted and well received in the video game world as well: God Of War and Hades are two of the more main-stream examples of this form of transmedia storytelling. It is easy to see why this works. Our lack of knowledge about ancient mythology leaves a lot to the imagination. These mythological games often function as extensions, they take characters from mythology, such as Hades’ Zagreus, and give them new dimensions, or add imagined characters, such as Kratos, to explore new perspectives on mythological tales.

Comics and Animations: Transmedia Within Games

Superheroes and mythologies are ways to adapt stories from other media into the gaming world. Games, however, have started to become transmedia concepts within themselves. Jenkins notes that players used to find URLs in their games to further delve into the narrative on websites. Nowadays, this is part of the game experience itself.

To name some examples: God of War has a comic that you can read on your Playstation and Apex Legends had comics inside of its own game. Rainbow 6 Siege produced an animated video, watchable within the game, to explain the story of Azami, one of its playable operators. All these forms of in-game transmedia have something in common: They expand on the story, but are not part of the general gameplay. The comics and videos are accessed through menus. Continuous, but isolated from the actual game.

Some games play with other forms of media as a more explicit part of the narrative. Control features live-action cutscenes and videos within its gameplay, for example. Skyrim, and The Elder Scrolls games in general, feature a lot of books detailing its history and world. One of those books is the thumbnail to this very article. In What Remains of Edith Finch, the player character of Edith reads books and comics too, yet the player is transported into a playable version of that narrative, quite literally transitioning from one media form to another. These mixtures of games as transmedia experiences within themselves are relatively new.

Games as a Source of Transmedia Storytelling

Games have often adapted other media, as we saw with superheroes and the like. While games have themselves been a source for other media before, such as the Tomb Raider movies, it has not always been with great success (such as the Super Mario Bros. movie…or the Tomb Raider movies).

Lately, the adaptation of games into other media has seen a resurgence, and one with positive reviews. Detective Pikachu and the two Sonic movies have been relatively well received, but the stand-out transmedia narrative has been the Netflix series Arcane. It is still one of the highest-rated TV series on IMDB at the time of writing this post. Turning game franchises into movies is, once more, not new. The reception and quality of the media created, however, is changing for the better.

These adaptations are often a form of multiplicity. Arcane does not follow League of Legends lore to the exact letter and it can not be seen as a direct continuation either. It adapts League of Legends’ lore, but lightly strays from it at points, when it makes more sense for the story the show is telling. The game is also far further along in its own lore than the series is, leaving the show trailing the plot, in a sense. Simply stated: Arcane is an extension. Similarly, the Sonic and Detective Pikachu movies follow their own story, rather than adapting, they extend. All these stories extend understanding of their characters, but do not form a direct continuous plot with the games they are inspired from.

Game Genres as Transmedia

An interesting development in the gaming world is when games change their genres, such as God of War changing from an over-the-top hack and slash game to a more narrative-driven game about fatherhood.

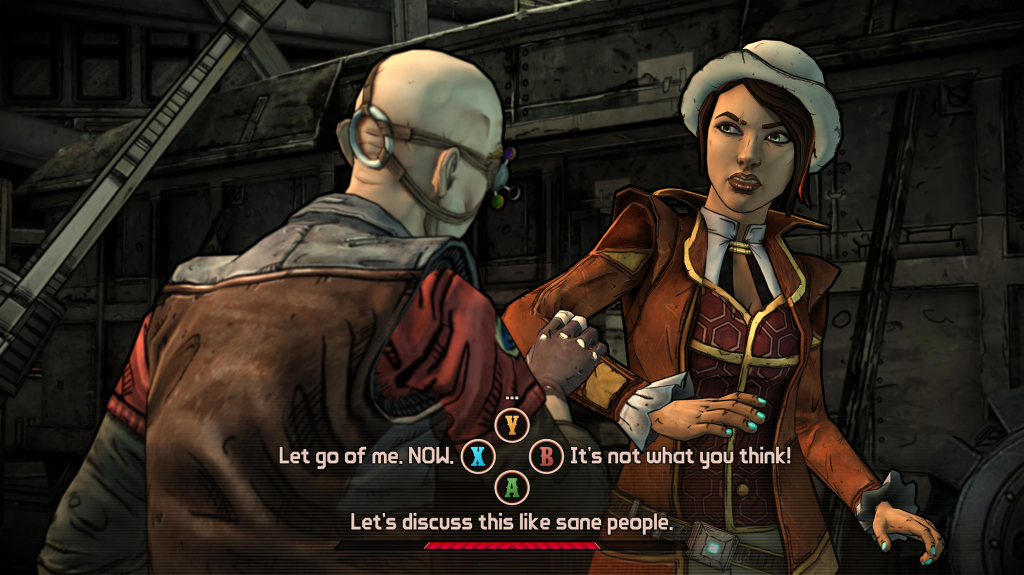

Some of these genre changes can almost seem like media shifts in and of themselves. A great example of this is Tales from the Borderlands. This game changed the otherwise comedic first-person loot and shoot game into a more serious and emotional narrative tale. The way the player interacts with Telltale games is entirely different than with the Borderlands franchise. Players interact with the environment fairly lightly, and influence the story through dialogue options and choices, leading to some mockingly calling this genre a ‘walking simulator’. This genre shift is so drastic that one might as well be playing a different medium, a transmedia narrative with continuity. Are those ‘walking simulators’ a different media form when compared to other video games? It is an interesting question, and a good reason to keep an eye on how this develops.

History as a Transmedia Narrative

The final, but important note, is that history can be viewed as a transmedia story. Lähteenmäki wrote a quite extensive essay on how Jenkins’ definition of transmedia relates to historical stories. The most important point to my post, is that historians create a sort of source narrative of history, one which other media use to create products from, and one of these media is video games. It is undeniable that some games interact with history, such as the Assassin’s Creed franchise. Lähteenmäki first learned about Romans from Asterix comics, and it stands to reason that gamers will learn of history through their games as well. This also means that transmedia concepts of multiplicity, continuity, and the others, can apply to historical games. They might tell narratives in which history is altered, in which history is presented in an alternate universe. Games like Detroit: Become Human even reference history while being set in the future.

Viewing (historical) games through this transmedia lens can help us understand not just how games relate to other media, but how they tell stories, and how they construct narratives of history.

P.S. Some readers might be wondering why I haven’t written about Homestuck. It is a full transmedia experience, with a narrative that moves through games, reading, animations and the like, after all. It would be honest to say that the warning of the work being around 8000 pages has been a bit of a hurdle to begin investigating this project, but, if I happen to do so, I expect to write about it too.