This fourth article in a series of deep dives into alternative historical depictions of Africa and Colonialism in video games focuses on Ethiopia. In its quest for modernisation, Ethiopia looked east to Japan and the Meiji movement. The Historical Flavour mod for Victoria II simulates Ethiopia’s development throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century. How is the legacy of the Japaniser Movement represented?

Introduction

The Solomonic and Yamato dynasties of Ethiopia and Japan are some of the oldest continuous monarchies of their respective continents. It is therefore hardly surprising that one royal house looked at another for inspiration at the advent of the 20th century. The Ethiopian intelligentsia took a keen interest in Japan in the early 1930’s and the 1931 constitution of Ethiopia, the first piece of modern legislation after centuries of unwritten medieval law, was modeled after the constitution issued under emperor Meiji of Japan. Its primary author, Ethiopia’s minister of finance Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam, formed a clique of like-minded intellectuals around him known as the “Japanisers”. Japan’s dramatic metamorphosis by the end of the 19th century from a feudal society—like Ethiopia’s—into an industrial power attracted them. For these young, educated Ethiopians, Japanization was a means to an end—to solve the problem of underdevelopment. Japan’s rapid modernization, after all, had guaranteed its peace, prosperity, and independence, while Ethiopia’s continued backwardness threatened its very survival.

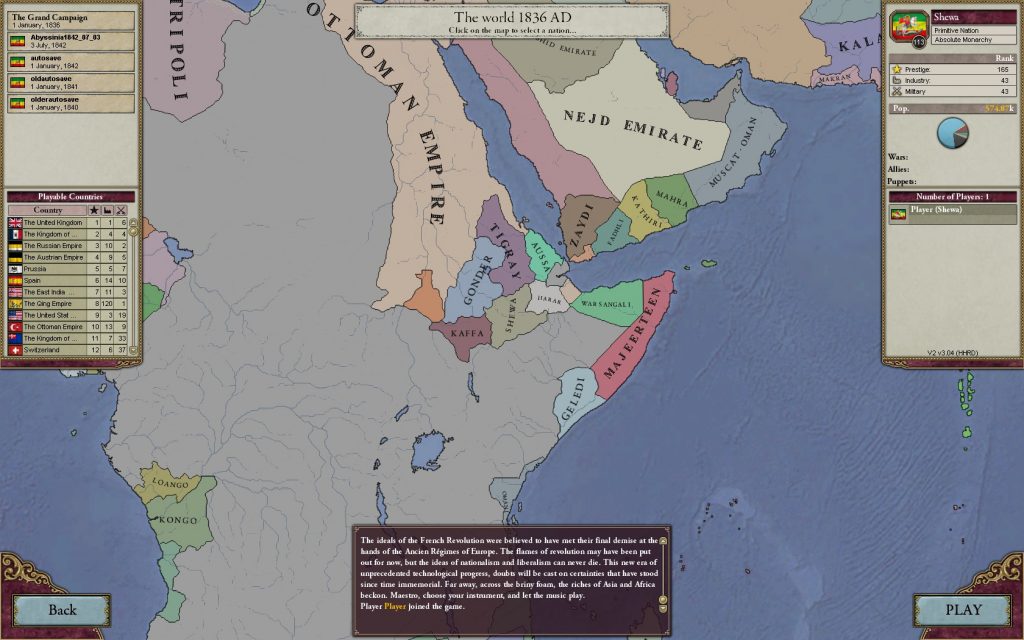

Modernisation, or “Westernisation” as it is called, is a primary game mechanic for non-European nations in Victoria II. The Historical Flavour Mod (“HFM”) builds upon the base game’s foundation by adding a variety of historically accurate nation tags in Africa, including in Ethiopia. The player is taken through the concluding chapter of Ethiopia’s Zemene Mesafint (warlord era) between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries and can unite the various princedoms in a war of unification not unlike the Meiji restoration in Japan. The rest of the game is then focused on internal development and modernisation, for which Ethiopia has a number of options which will be explored in this article.

End of Zemene Mesafint; Road to Modernity

After 86 years of internal conflict between the princes of Ethiopia, prince Kassa Hailu consolidated power following the battle of Derasge in 1855 and crowned himself Tewodros II, the first “king of kings” in almost 100 years. While Tewodros II envisioned a grand modernisation of his empire, he was continuously preoccupied with fighting against dissent. Tewodros sought British aid in a “crusade” against the Ottoman Empire who were funneling weapons to the Islamic Oromo people living in Ethiopia’s interior in an attempt to destabilise the state, but such aid never arrived. The British refused to respond to Tewodros for three years. Insulted, the emperor imprisoned the British mission to his court, which prompted Britain to send a punitive expedition to depose him.

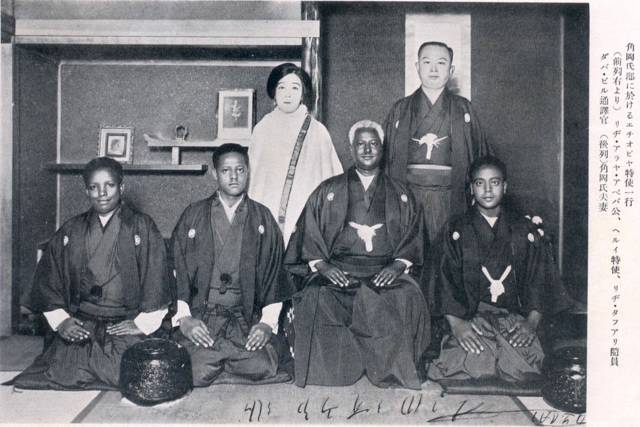

Subsequent emperors such as Yohannes IV and Menelik II would face the same issues of Tewodros; constant territorial encroachment by European and Ottoman forces and internal religious and ethnic strife pitting the under-kings and princes against imperial authority. Modernisation was seen by Ethiopian intellectuals as the only path forward if the nation wanted to remain truly independent, but a feared loss of cultural authenticity dissuaded the more conservative-minded aristocracy from embracing the west. An outside perspective was needed and eventually found; under Queen Zawditu and regent Haile Selassie I a group of progressive and educated Ethiopians the empire would look to Japan. Japan was seen as a model for its successful adoption of Western learning and technology to the framework of a non-Western culture. Ethiopia adopted a new constitution in 1931 modeled after the Japanese Meiji constitution and soon after a diplomatic mission was sent to establish closer ties between the two empires.

The following year, Heruy Wolde Selassie, the Ethiopian chief palace administrator, published Mahidere Birhan: Hagre Japan (“Japan, the Source of Light”). In this document Heruy outlined that Ethiopian and Japanese history were strikingly similar and that to be successful Ethiopia must emulate Japan more. Heruy compared the Tokogawa era in Japan (which lasted from 1603 to 1867) to the Zemene Mesafint in Ethiopia, but noted that the power of the under-kings in Ethiopia had not been curbed as much as that of the Daimyōs (Local feudal lords who had traditionally been in power for centuries) in Japan. Japan’s success against Russia in the war of 1905 was also of great interest to emperor Haile Selassie himself, who sought to replicate this success against Italian aggression.

Japanese-Ethiopian relations continued to prosper in the 1930’s. A massive irrigation project of Lake Tara in Ethiopia was undertaken by Japan and 100.000 Japanese planters settled in the region. There was even some international commotion regarding a “royal’ marriage between Prince Lij Araya Abeba of Ethiopia and Masako Kuroda of Japan (neither of which were from their countries’ ruling dynasties) but Italian and general European resistance against Asian expansionism in Africa as well as the Japanese government’s diplomatic ties with Italy and Germany led to a general breakdown of relations with Ethiopia. Of the 100.000 planters only 15 actually settled around Lake Tara and by 1934 only 4 of them were still there. Japan’s economic interests in Ethiopia never went beyond their exploratory first stages, diplomatic relations were never truly formalised and European outrage regarding the controversial “royal” marriage led to the whole affair being blown off.

Ethiopia in Victoria II’s Historical Flavour Mod

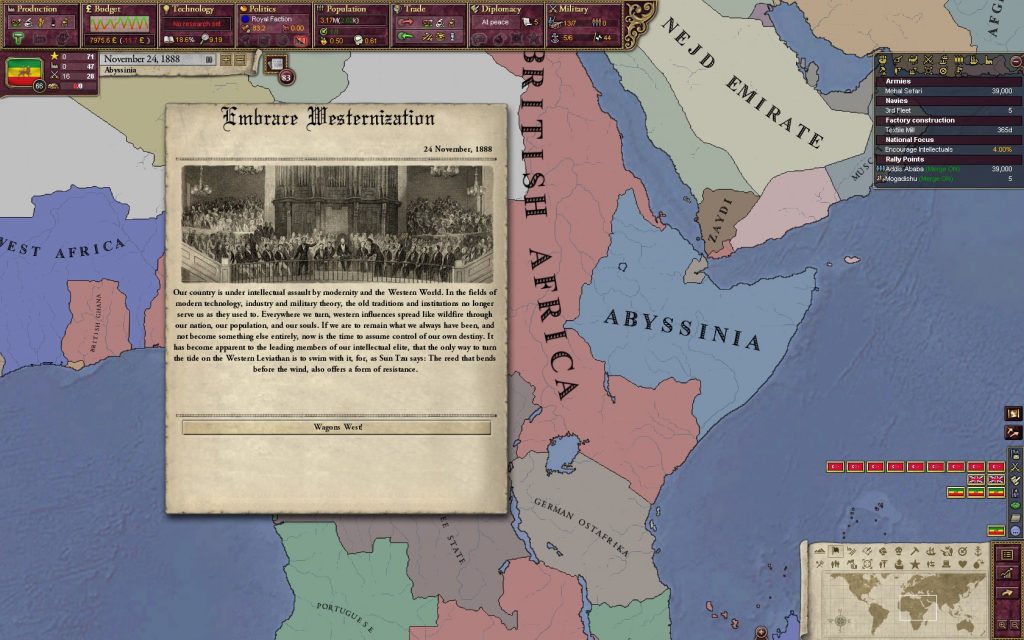

Unlike the base game where Ethiopia simply already exists as a united entity on the map, the Historical Flavour mod places the player in the middle of the Zemene Mesafint. The various kingdoms all start out at 0% “westernisation” out of 100 that is required to rise from the status of “primitive” to “civilised”. These terms are a carry-over from the base game and come with their own set of issues which this article will go into more detail on. Victoria II’s “westernisation” mechanic assumes non-western nations have to adopt systems of governance, army structures and national ideology from a Great Power to achieve modernisation but overlooks the primary non-western factor in this equation. The Historical Flavour mod makes some effort to remedy this, as will become clear once Japan enters the picture.

Each princedom starts out with two modifiers related to the Zemene Mesafint which expire on January 1st 1866. This is where historians place the end of pre-modern Ethiopian history, about a decade after the coronation of Tewodros II on the 11th of February 1855 when he had fully consolidated his power. The player is free to end the Zemene Mesafint as any of the kingdoms whenever they manage to become the unquestioned ruler of Ethiopia through conquest. The kingdoms all have “core territory” in each other’s provinces so wars of territorial integrity can be declared immediately, which allows a skilled player to unify the region in less than a year. There is a gameplay incentive to quick unification as well, as it creates a larger window in which Ethiopia can begin catching up with the West.

“Westernisation” involves gathering research points to reform aspects of the nation’s society and filling up the progress bar until it reaches 100%. Western nations will incur much less international infamy for taking territory from non-westernised states and can even annex them completely after the Berlin conference of 1884. The land without nation tags seen on the initial map screen is not empty either; it contains population and resources western nations can exploit by colonising it as soon as they have the technology to sustain a settlement there. The Historical Flavour mod dynamically simulates European colonisation efforts in Africa as going from coastal settlements to full-scale internal colonisation over the course of the 19th century.

Once the “Westernisation” process is complete Ethiopia will be known as a “civilised” nation and other nations can no longer invade it without incurring a massive infamy penalty like they would when invading European nations. The technology tree and industrialisation will also become available, which can allow for a rapid catching up in international standing. The Berlin Conference in the Historical Flavour mod comes with a mechanic that resets the opinion of European nations towards African states, making any colonial border shared with them highly likely to escalate into a war where a “protectorate” is established and Africans are annexed wholesale into the colonial system.

The quickest way towards “Westernisation” is being in a Great Power’s sphere of influence. This comes with its own drawbacks such as a puppet economy and deindustrialisation as discussed in the previous article but will allow for the direct import of Western arms and equipment as well as an overhaul of the military along Western standards. Traditionalists within the state will not be happy with these developments and aggravating them too much can lead to uprisings which detract a random percentage off your “Westernisation” progress. For African states that want to survive the Scramble for Africa and achieve parity with the West, embracing modernity through “Westernisation” is their only option.

Westernisation? Easternisation!

Or, is it? Victoria II’s event writing seems to suggest that modernisation for non-western states will always mean adopting European systems and beliefs, but the rise of Japan from the mid 19th century onwards and the Japaniser movement that emerged in response in Ethiopia tell a different story. After the Daimyōs of the Tosa, Hizen, Satsuma and Chōshū clans overthrew the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1869 they abolished the feudal system Japan had been governed under for centuries, reinstated Emperor Meiji as the sovereign ruler and adopted a new constitution based on a mix of English and German legislation. This could be seen as an embracing of “Western ideas” and therefore as ”Westernisation”, but the reality of this event is more complex than that. Under the Tokugawa shogunate Japan was in the so-called Sakoku period, totally closed off from the rest of the world and focused inward. The unrivaled power of the Daimyōs combined with the deliberate exclusion of technological advancements caused Japan to stagnate while the world around it, particularly the West, surpassed them in martial prowess. When the anti-Tokugawa alliance of clans overthrew the Shogunate the traditional ways of fighting with swords and bows had already begun to be phased out by the relatively small trickle of Portuguese and Dutch guns that came in at the few sanctioned trading posts on the Japanese coast. Adapting to modernity on one’s own terms is preferable to having modernity forced upon you by outside forces, and the movement behind the Meiji restoration understood that.

The new Japanese Empire then undertook a program of rapid industrialisation and in political spheres an ideology was conceived that considered Japan the center of a sphere spanning all of Asia, to keep western colonialism at bay. In 1905 the whole world was shaken by the revelation that this new, modern state could take on the west on the field of battle when it clashed with a woefully unprepared Russia in Manchuria and won.

This was the first major military victory in the modern era of an Asian power over a European nation and a crucial stepping stone in the Japanese path to Great Power status. It firmly placed Japan in a position as a model to be emulated by non-western states looking towards modernisation while retaining their cultural distinctiveness. Japan looked at Asia and at Africa as regions to expand its influence in, and Asia and Africa looked back. The term “Westernisation” as it is used so extensively in Victoria II and the Historical Flavour mod by extension is therefore a bit of a misnomer. Modernisation is desirable for non-western states, both from a historical perspective and in terms of in-game mechanics, but this does not mean the devastation of one’s culture just to attain a degree of parity with the forces of cultural destruction. Nations that have had similar histories such as Ethiopia and Japan rightfully looked to one another to stand on their own two feet in a world that was rapidly outpacing them. In Ethiopia’s case the Zemene Mesafint and the lingering power of the under-kings that remained in its wake are comparable to Japan, Meiji and the Daimyōs. Ethiopia, like Japan, walked the tightrope of maintaining its cultures and traditions in a world that grew ever more hostile to states that could or would not compromise with modernity.

If there is a lesson to be learned from Ethiopia’s history since the Zemene Mesafint it should be that Western powers were too caught up in their own affairs and much too worried about a challenge to their hegemony in Africa to consider partaking in a reciprocal agreement with Ethiopia so they might one day sit at the same table. This is why they took every possible opportunity to stifle Japanese investment into Ethiopia; it worried western powers greatly that an Asian power was expanding its horizons into “their” backyard. Ultimately though war between Ethiopia and Italy ended any potential deeper ties that could have developed with Japan, as well as the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Empire. Haile Selassie I fled the country and Ethiopia was made into an Italian colony. While Japan’s ties with Italy prevented them from seriously engaging with Ethiopia in our world, Victoria II’s mechanics allow for a historical approximation of what this relationship would have looked like had it truly come to fruition. While there regrettably is no direct representation of the Japaniser movement yet in the Historical Flavour mod through events and decisions for Ethiopia to enact the general “Westernisation” mechanic does allow for interaction and cooperation with Great Powers, no matter where in the world they are from. If Ethiopia has sufficient diplomatic relations with Japan after the Berlin Conference, then as a non-European Great Power may end up as Ethiopia’s strongest ally after 1884.

Notice Ethiopia (Abyssinia) is also pink, indicating they are protected by Japan.

The Japaniser movement in Ethiopia, however brief it may have existed in any viable form, sheds light on an alternative history of African self-strengthening along Eastern lines rather than those of the West. The Japanese ideology of Pan-Asianism and the ideas of Pan-Africanists in the post-colonial era share a fundamental similarity that warrants further research, particularly to determine the outside influences on Pan-Africanism following the rise of Marxism in Africa. A more tradition-oriented Pan-Africanism may have looked something like the Japaniser movement in Ethiopia if it had continued to exist after the 1930s. It also poses a challenge to the idea of “Westernisation” being exclusively a process of cultural self-mutilation to adapt to modernity. Non-western nations can rise to the challenge of modernity on their own terms and be extremely successful, like Japan.

Jochem ‘Guthixian’ Scheelings is an MA student in African Studies at the University of Leiden and Intern at VALUE. He is aiming to specialise on crossing the boundaries between gaming and academia in his own field of expertise and maintains a broad interest in all depictions of Africa in video games. His speciality is immersive historical simulators by Paradox Interactive. Tweet him at @Guthixian_VALUE