Last year July, we played Attentat 1942 during one of our streams. Developed by a team of historians and game developers at Charles University in Prague, it revolved around a particularly dark moment in Czech history: the Second World War and the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (and subsequent retaliation by the Nazis). Svoboda 1945: Liberation, the second game made by Charles Games was released on August 3rd. It portrays the situation in the German-Czech border region of Sudetenland just after the war. Once again, Charles Games have managed to make an amazing game, which will not only give you new insights into this often overlooked part of the war, but will also make you think about how heritage is viewed through different personal lenses. Here’s a short review, trying to not spoil the game too much for you.

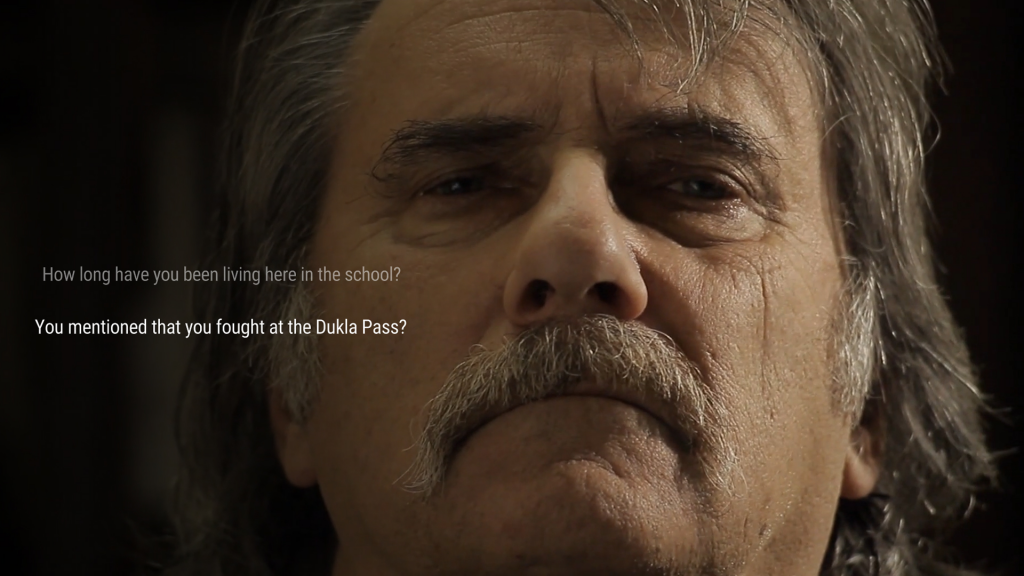

Like in Attentat 1942, the game portrays a situation that is not often portrayed in Western (European) media and games: the war in Central and Eastern Europe. The war in these parts of Europe is often overlooked in Western European history classes and historiography as well. This is even more so the case for the events just after the war, but before the Cold War had really started. Svoboda 1945 encompasses the years after the German capitulation in 1945. Set 20 years in the past, you play as a historical researcher sent to the town of Svoboda near the Czech-German border. You are tasked with reviewing the status of an old school building, which is set to be demolished, and need to decide if the building has historical or heritage value.

For those who are unknown with the history of Czech-German border region: known as Sudetenland, it was annexed by Nazi Germany before the war had started in 1938, after the Munich Conference (where UK PM Neville Chamberlain promised there would be ‘peace for our time’). Even though the area wasn’t completely ravaged during the war, it had left its marks. The period just after the war was also not without its violence. Retaliatory actions against those who collaborated with the Nazis weren’t uncommon in the entirety of Europe. But the Sudetenland, alongside other regions in Central and Eastern Europe, were different, as they were home to a large group of Germans. These people were all expelled from Czechoslovakia, often forcefully evicted with little notice and deported, even though many had lived there for their entire lives and in some cases, for generations. This is one of the poignant histories many are unknown with.

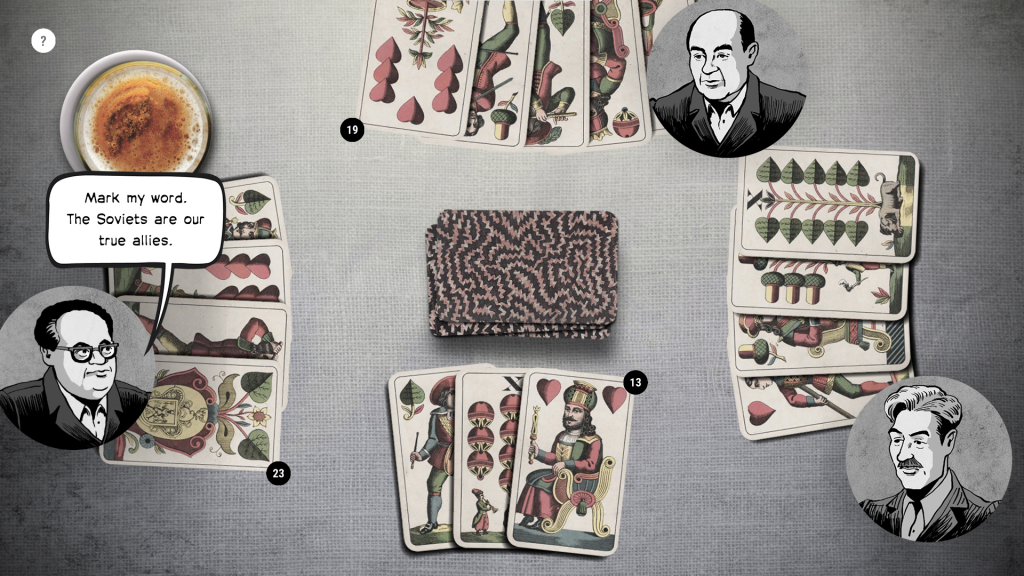

The expulsion is a central theme in Svoboda. It has shaped the history of the country, but also the relations between people living there. People who had lived there many years were forcefully expelled, leaving everything behind except for some clothes and small personal belongings. Friendships and relations were broken, and some people never knew what happened to their family members. New people also moved in, partly under the veil of collectivization. With the end of the war, also came the start of the communist era in Czechoslovakia. What started out as the desire for an independant Czech Republic, after the electoral victory of the communists, the Czechoslovak Republic was born. A satellite state to the Soviet Union, communist rule made life change in many ways. In a predominantly rural area, collectivization made tensions between people spark. Communist rule and collectivization, alongside the expulsion of many people, has left a deep mark on the society in the region. Svoboda portrays this period through personal stories of people affected by the new rule, on the positive and the negative sides. This makes for a nuanced story about the post-war period in Sudentenland. Charles Games’ modus operandi, making use of personal histories, once again proves to be vital in disseminating a larger informative narrative. However, Svoboda isn’t all about people. It is also about places.

At the center of the game is a school building in the village. The school was not only used as a school before and during the Nazi occupation, where many were brainwashed with fascist propaganda, but was also used to round up Sudeten Germans who were to be expelled. This one location tells its own personal history of the pre-war, war and post-war period. More than one of the personal histories you get to know along the way cross this building, and as your research into the building progresses, you learn how vital a building can be for the construction of memory.

Aside from telling a gripping story of post-war Czechoslovakia, where you’ll undoubtedly learn more about this period and region, Svoboda also makes you think about the value of heritage. Especially about what heritage specialists and historians would call ‘dark’ or ‘difficult’ heritage. Difficult heritage could be used as a description of heritages which can have negative connotations to not only people living in the vicinity, but also people visiting the location. However, they can often tell an important story, or have architectural, historical or personal value. Examples of difficult heritage are found all over the world. In Europe, the Second World War has left many of these difficult heritages. Think of the Nazi Party Grounds in Neuremberg (British anthropologist Sharon MacDonald used this as a case study to coin the term ‘difficult heritage’), Nazi Extermination Camps in Eastern Europe, or the ‘Muur van Mussert’ in the Netherlands. But difficult heritage isn’t a purely European phenomenon, nor is it always linked to the Second World War. Other examples are the slave fortresses on the West African Coast, the Maximum Security Prison on Robben Island and Seodaemun Prison in Seoul.

Svoboda takes a place of ‘difficult heritage’ and lets you decide what to do with it. Destroy it, or make it a monument. Both options have downsides, as is explained through the personal histories in the game. It all boils down to your own views on heritage, and I think there is no one good way to deal with difficult heritage. It’s a useful reflection on the way we nowadays approach heritage, and it starkly contrasts how heritage was handled fifty years in the past.

This review is mostly geared towards the more historical content in the game, but it wouldn’t be a game review if I didn’t say anything about the actual game. Like Attentat, Svoboda is more of a point and click digital graphic novel than a full-blown game. You spend most of your time clicking dialogue options or speech bubbles than actually gaming. However, that is only supportive of the game which is in front of you. Charles Games have livened up this clicking with some small mini-games, in some you just find items and click, in some there’s actual tasks to complete (like developing photographs). Changing up the clicking with some interactive mini-games is very fun, and also supportive of the story.

All in all, Svoboda is another brilliant game by Charles Games. They’ve once again managed to portray an often unknown history in an understandable way, and you’re bound to learn new things. ASide from that, they’ve also managed to make you reflect on the use of heritage, especially the heritage that remembers us of dark times. It will only set you back about €14, so Svoboda is definitely worth checking out!

Svoboda 1945: Liberation is now available on Steam. More info on the game and about Charles Games can be found on the studio’s website or Twitter.

Omar ‘oomzer’ Bugter is a Cultural Historian from Utrecht. Since interning at VALUE, he’s stuck around, mainly working on the Interactive Pasts website and the weekly streams. He wrote a thesis on Sid Meier’s Civilization VI and mods, so knows this game very well. He likes many other games, including F1 2020, Hearts of Iron, Mount & Blade and Crusader Kings III., and is VALUE’s in house city builder connaisseur. Tweet to him at @oomzer if you want to know anything about Civ or city builders.