In this new series, I will explore how games tell stories differently than other media. We start by looking at how games use immersion and player control, with The Last of Us as the main example.

Spoiler Warning: This post will spoil major plot points of the first The Last of Us game. NOT the second game, so if you were worried about that, don’t be. If you want to play The Last of Us, you might want to save this post for later.

In my last post, I explained how games and other media can tell the same stories within the same universes. Now, I will start exploring how games handle narratives in their own way(s), in this new series of posts called How Games Tell Tales.

The first game we will look at will be The Last of Us, a zombie survival shooter from 2013, although it has seen a remaster later on, and a remake very recently. With an HBO series upcoming that will explore the story of the game, it would seem like now is a perfect time to explore how The Last of Us tells its story in a way that is unique to video games. This post shows how the notion of “hyperreality” and control impacts the way an audience interacts with the medium of video games.

Hyperreality and Player Control

I mentioned in my last post that I would discuss immersion in video games very soon. I actually think that game narratives explore a unique sense of immersion: hyperreality. The idea of “hyperreality” is that, at a certain point, we become unable to distinguish between reality and a fake version of reality. Umberto Eco mentions Disneyland, where we can believe, just for a little bit, that something like Goofy is a part of our reality. So how does this apply to games? Matt Sautman claims that games cross this border a lot, as we talk about stories in a game with “I climbed the mountain”, not “The character climbed it”. We experience games as our own experiences, as if we lived them. Sautman further states that a player’s control over the game is why this line is crossed, as that is how this experience comes to be. I would argue that this sense of hyperreality can be very abstract, and go beyond humans. When I play Stray, I do not just experience the game as a cat, I tell other people that “I” walked over those roofs and made those jumps, as if I became a cat. And all of this is caused by being in control of a cat on a screen.

The Last of Us has an excellent example of this impact player control and hyperreality have on a player, as it plays with these as narrative tools. At the start of the game, we play as Sarah, and, as with Stray, “I” walked down those stairs and checked Joel’s phone. Then, an accident happens, and Sarah can no longer walk. Joel, her father, has to carry her. The game switches control here, from Sarah, to Joel. But, Sarah is still moving when the player moves the joysticks, as Joel is carrying her. As such, the change of control does not feel abrupt. “I” am still experiencing what Sarah is going through, but I am now also Joel. Once Sarah dies at the end of the prologue, and the player has to control Joel after a time skip, this change of control does not abruptly break immersion, simply because there was a period in between where we played as both. I already was Joel before this point.

Later in the game, Joel gets injured, and instead of his new companion Ellie becoming playable right away as she helps him, we play as Joel, until he falls unconscious. The game fades to black, and we suddenly find ourselves playing as Ellie, hunting a deer. This change of player control is not smooth, it is sudden, unexpected. It adds to the tension of the game, as we do not know what happened to Joel, and have switched characters before, when one died. Is Joel dead? Why are we playing as Ellie if he is not? This, very shortly, takes us out of the hyperreality, we have not played as, or been, Ellie before, and we have to play her without any preparation. I am not ready to be Ellie, yet. This usage of the hyperreal to unnerve is unique to a medium in which the audience has control.

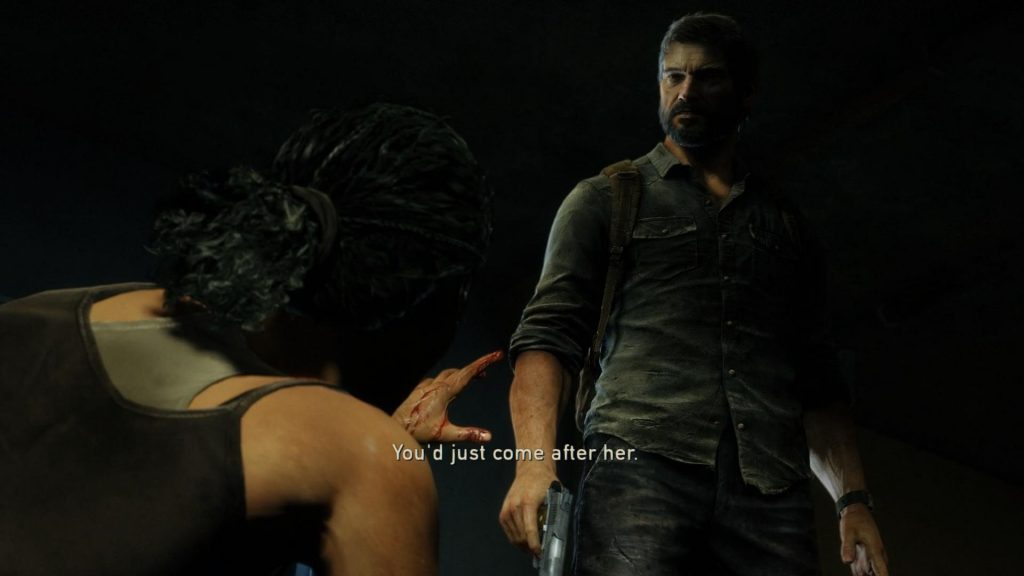

When Hyperreality Breaks: Playing the Reprehensible

As mentioned, the sense of hyperreality leads to players describing events as having done them themselves. However, this notion can break, especially when the character does something morally reprehensible. When I play as Joel, I am fine with describing his acts as mine for most of the game. However, I find myself describing them as Joel’s acts, when, at the end of the game, he shoots his way through a hospital to save Ellie, and kills Marlene, who is unarmed. I do not want to feel like I am Joel at that moment, and explain his actions as “I can understand why Joel would do this”, or by explaining how Joel felt at that moment. In a sense, there is cognitive dissonance here, I both am Joel while playing, but want to believe I am not when his actions are, to me, inexcusable.

So, games can play with the hyperreal, the sense that we are the characters on the screen. They can use this as a narrative tool, to increase suspense, to shock or unnerve. They can break this hyperreality on purpose, by making us do acts we might disagree with, as we become increasingly uneasy with who we are within the game’s world. It is a unique version of immersion, and one that I believe to be wholly unique to the medium of video games.