In this third installment of How Games Tell Tales, I will discuss games that offer a large amount of player input. Using Detroit: Become Human as an example, I will explore how such choices can work, how most choices are not as meaningful as they seem, and how this intertwines with the concept of intended play.

Spoiler warning: This article will majorly spoil Detroit: Become Human. If you are at all interested in this title, I would recommend you play the game before reading on.

Last time, I discussed Nioh’s simulation of history. This week, I aim to explore how games offer the player direct interaction with their stories. Some games offer serious choices to players, which impact the direction a story will go into. One such a game is Detroit: Become Human. This game is not without its fair share of controversies – especially for its references to history – which I will discuss separately in another upcoming article. Today’s post will focus on the narrative tools this game uses: giving the player choices in its story.

How the Choices Work

Games such as Detroit: Become Human (referred to as DBH from now on) often get compared to Telltale games, a specific type of narrative game created by the now-defunct Telltale studio. In these games, the player often plays through what is best described as interactive cutscenes, where a scene plays out, and the player gets a choice, as shown in the banner to this post. These games are also at times called ‘walking simulators’, as – in between these cutscenes – players mostly walk through a room or environment, interacting with objects and talking to people.

The player plays as three androids in this futuristic game: Kara, who escapes an abusive human owner, and becomes a deviant – a sentient android – right at the beginning of the game. Markus, who leads an android uprising against the oppressive human regime. And Connor, a law enforcement android, who struggles between staying a mindless machine, or becoming a deviant himself.

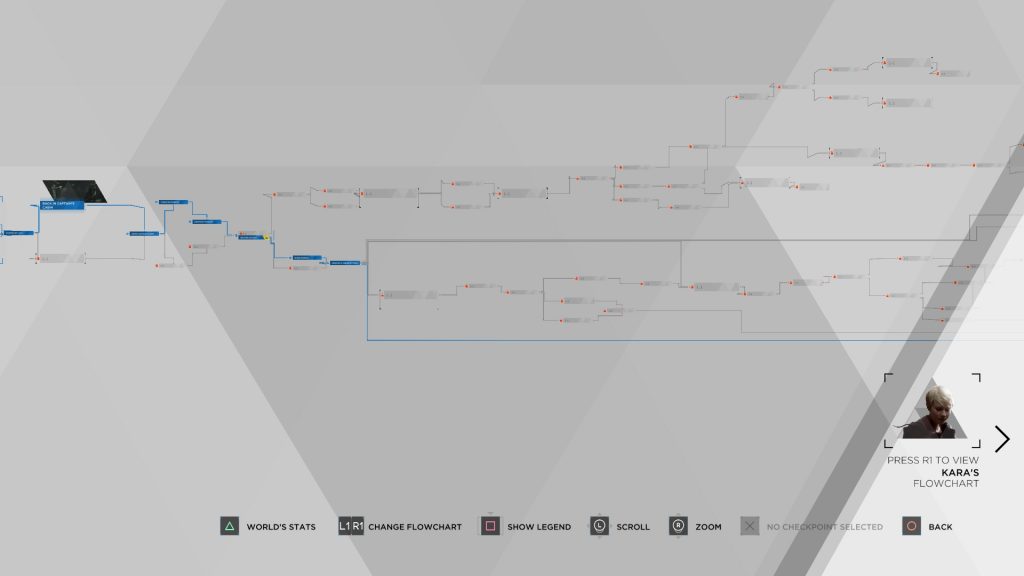

As these androids, the player gets to make choices which impact the story. How such a control over the story works becomes more clear with the game’s own flowcharts:

As you can see, it is kind of like a “choose your own adventure” book. The player picks a choice in a cutscene or in dialogue with other characters, which leads to a specific version of the adventure. It seems there is a lot of freedom here, with all these branches of a story, there must be a lot of different outcomes. Well, that is where a system like this becomes interesting.

Nothing Branches Forever: The Illusion of Choice

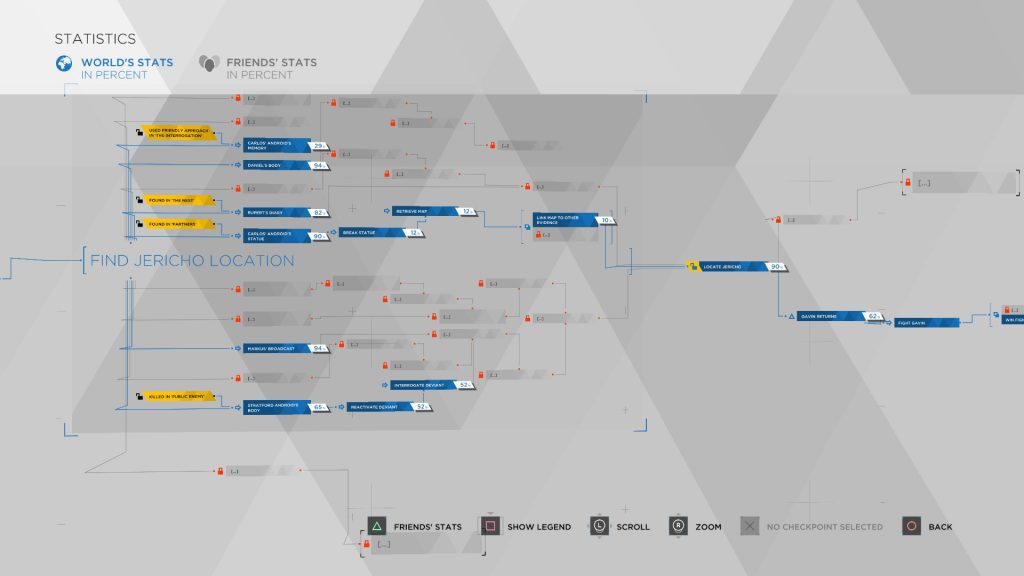

Let’s look at another flowchart:

In this chapter, there are a lot of choices, but not all of them branch into other consequences, and, crucially, they all lead to one major outcome: Discovering Jericho, a place where deviants hide. In fact, this chapter only really has three outcomes: Connor’s line of androids gets decommissioned, and his story ends. Connor gets killed, in which case he returns, because as a law enforcement android, his memory can be downloaded from the cloud and can be put into another Connor model. Finally, Connor finds Jericho, and goes there.

Markus’ choices are similarly limited, and are even spelled out by this survey in the game:

What this shows is a flaw with this type of narrative design: One can only branch out choices for so long. Eventually, the choices will re-center around a few possible endings: Kara dies or survives, Connor gets decommissioned – which is essentially death -, becomes deviant, or stays a machine, Markus succeeds in a peaceful rebellion, or dies, or fights to the bitter end.

There is an illusion of choice to this. The player can think they are making an impactful choice, but it might actually be one of the branches that does not continue further, or leads to the same result as any other choice. Some games do not make this illusion visible, which means players can only notice it on repeat playthroughs. Through the flowcharts in Detroit, however, players can see exactly how much their choices mattered. It is for this reason that I chose to discuss this game for this topic, as these flowcharts make the flaws in this narrative design more explicitly visible.

It should be noted that these flowcharts are not directly available during normal gameplay. The player has to go out of the game and select a chapter to play in order to see the flow chart in the way I have shown them here. While the flowcharts are just not directly shown, it is still pretty easy to find them and expose this illusion of choice.

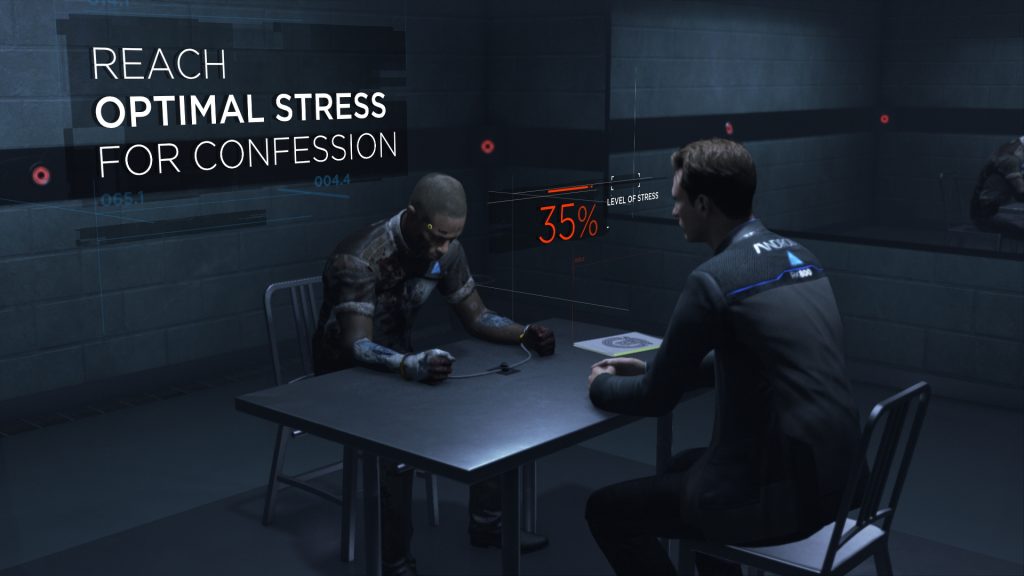

A great example of how this works in gameplay is the interrogation scene. It feels very intense, but also makes it very explicit that the choices only matter as long as they reach the optimal stress level of the suspect, or not. If I change the android’s stress level to just below the optimal zone, nothing will really change. If I get into that zone, I get a confession. Crucially, if the android gets too stressed, he will self-destruct. That is a major consequence right? Not really, as the android’s memory can now be used in the Jericho flowchart above, to still be able to find Jericho later on, and his self-destruction does not change the rest of the plot. Whatever choice you make, the android will prove useful to the investigation.

This problem, however, does not end with the illusion of choice.

We All Make Similar Choices

The game also has a feature that shows the choices all players have been making:

You might have noticed the same thing I did: A lot of these choices were made by a vast majority of players. This is something that is known within games such as these. In Mass Effect, the player can choose between Paragon (good) and Renegade (evil) choices, and 92 percent of players picked Paragon. Similarly, in Detroit: Become Human, certain choices seemingly just make sense to make. So, not only do choices lead to similar or the same outcomes….most players end up in the same scenarios because they make the same choices, leading to 90% of players locating Jericho.

Is it even a choice then? What is the point of the choices no one really makes? One choice is to detonate a dirty bomb in Detroit. To get to that point, the player needs to make many violent and potentially abhorrent choices. If a player fails all quick-time event button presses in a chase, Connor can die. Surely, that is not intended to be played through, as no one would fail all of those presses, right?

Intended Play

5 years ago, Dan Olson, also known as “Folding Ideas” on Youtube released a short video about “Intended Play”. The idea of it is this: If the game has a reaction to what you do, then that act is intended to be done. If the game did not intend for players to do a certain action, then it would not have coded a reaction to it.

While Olson uses Dark Souls and The Stanley Parable as his examples, games such as DBH perfectly show this concept as well: there are parts of the game that almost nobody has seen, with choices and outcomes that seem gruesome, undesirable, and immoral. Yet, these outcomes are part of the flowcharts and story branches: they are intended to be played through, to be explored. Even the example of quick-time events is intended, as the game has responses to the player failing every single one of them, as shown below.

The player is meant to see the good and the bad versions of this story, they are meant to laugh at Connor falling as they do not touch the controller during a quick-time event, and they are meant to grimace at the outcome of choices they would never make, but make just to see what happens if you did this other thing. Even if the player’s goal from the get-go is to have the worst possible outcome, the game has a response to that, by giving the player that outcome.

Branching storylines such as these are limited by the time and money that can be invested in creating the choices and branches. Many choices can end up being unimportant, and many outcomes are the same. Yet, it is still an interesting way in which video games can offer a narrative with more control than any other media, and I look forward to what these types of games do in the future.