In this sixth edition of How Games Tell Tales, I will discuss how the Beginner’s Guide treats the tension between authors and their audience, through a story in which a developer’s games get interpreted.

The last How Games Tell Tales post was a while back, but we’re back with more!

‘The curtains were blue not because the author was depressed, but because the author liked the color blue.’ This quote is found in various forms, and its origins are unknown. Often, it is used to criticise professors and literary critics who are argued to assume everything in a work has to have a ‘correct’ meaning, as seen in this post. In these cases, the quote seems to be aimed at bad teaching, rather than wrongful literary analysis, in which professors are said to want a ‘right’ answer to the meaning of something, as also claimed in that post.

Nevertheless, the quote makes an interesting point: sometimes an author’s intentions are different to what an audience reads into a work. There is a tension there. What if the author’s intentions conflict with that of the audience? Contemporary critics would argue for the death of the author at times, a concept in which the author’s intentions are less relevant if a different reading can be found within the work. This interpretation has its uses, mainly when an author writes problematic works, and argues the problems do not exist, or were not intended. Using the death of the author, it can be argued that the problems are still there, and should be confronted.

But can art criticism and interpretation go too far? This is what the Beginner’s Guide deals with. More than ever before I would argue that you should play the game before reading this article. It’s a short game, you could even watch a playthrough, but this article will have less impact if you haven’t experienced it yourself.

The Beginner’s Guide To Story Ownership

The Beginner’s Guide features a fictional narrator, Davey, and a fictional developer, Coda. Davey claims to be friends with Coda, and will interpret their games for us. Throughout the game, Davey alters Coda’s games, skipping sections and giving the player solutions to puzzles. Davey starts to interpret Coda’s games, and what they say about Coda.

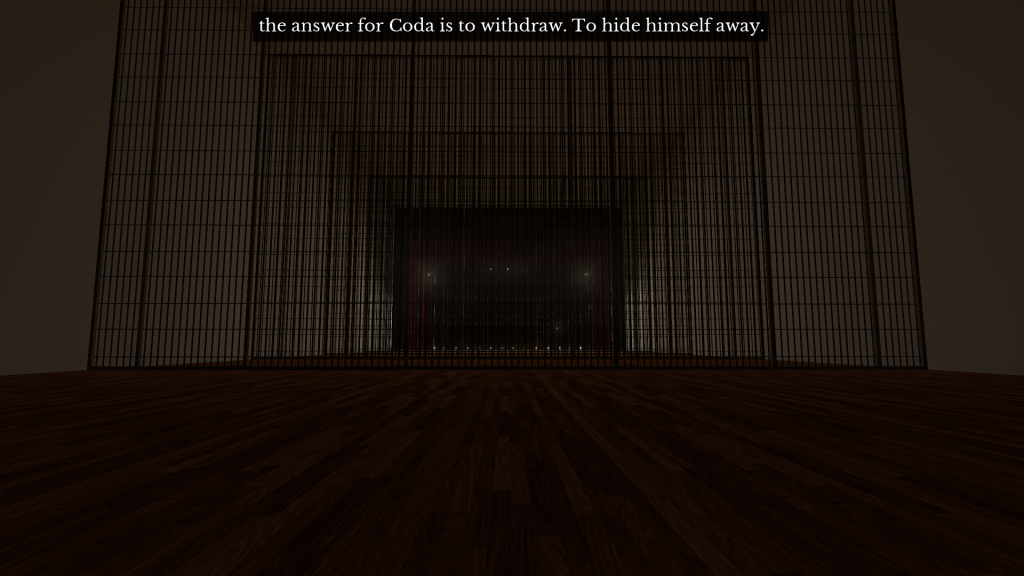

He starts to assume that Coda is mentally unwell once Coda repeats a prison game over and over, and starts to feature rather depressing dialogue within his games. Davey argues that his friend must be depressed, that making games must be what is stressing him out. And he does so by interpreting what he assumes to be metaphors and allegories in Coda’s games.

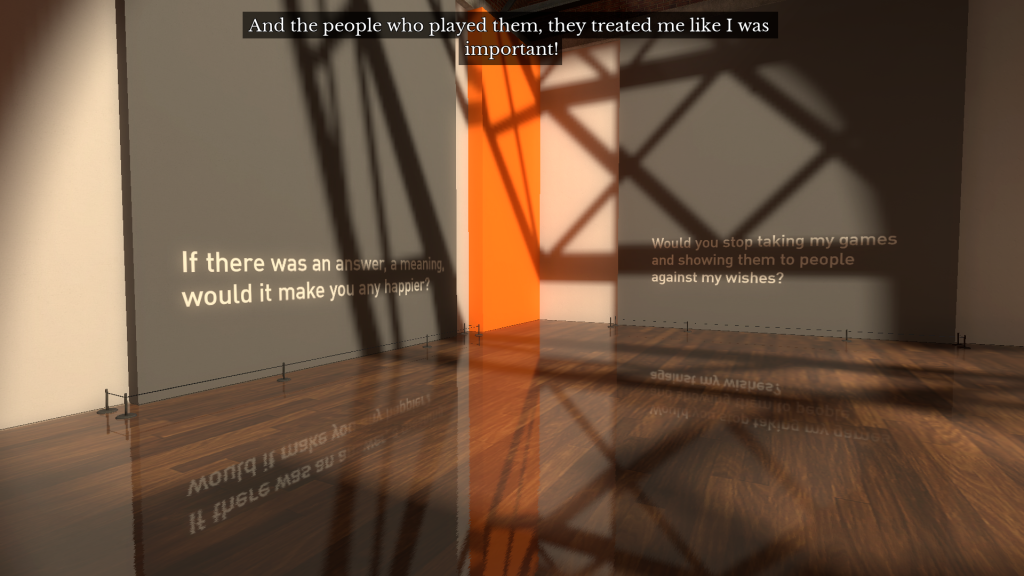

But then, at the end of the game, it turns out Coda is not depressed by making games. It is Davey, who is showing Coda’s games to other people, who is interpreting Coda’s mental state, who is changing the games themselves. Davey is mentally impacting Coda, and Davey himself has an issue. As Davey starts saying at this point, he wanted to feel important and seen, and did so by sharing Coda’s games with others, and interpreting them for the audience.

This is where The Beginner’s Guide deals with the tension between an audience and an author, between literary criticism and the author’s perspective. And crucially, it is about who owns the story of a product. Davey, the critic, claims ownership of a certain reading of Coda’s games, corrupting them for Coda in turn. He shares this reading with everyone else, sharing an image of Coda that Coda himself might not agree with. More than a death of the author, or a misreading of a product, Davey claims a truth to a work, claims that one interpretation is better than another, and claims this interpretation to everyone willing to listen to him.

This is all close to a blog post written by the real Davey Wreden, creator of the Stanley Parable, and this game as well. When The Stanley Parable started getting Game of the Year awards, Wreden wrote a blog post. He explained how he felt like he was losing ownership of his own art, as if the opinions of others trumped his own. Similarly, the narrator version of Davey is claiming ownership of Coda’s story, which poisons Coda in turn. The Beginner’s Guide, as such, deals with this apparent tension between author and critic that Wreden himself has brought up before. Of course, stating that this game is saying something about the real Davey Wreden would be to do what the narrator is doing; making assumptions about the author.

The Curtains Weren’t Even Blue

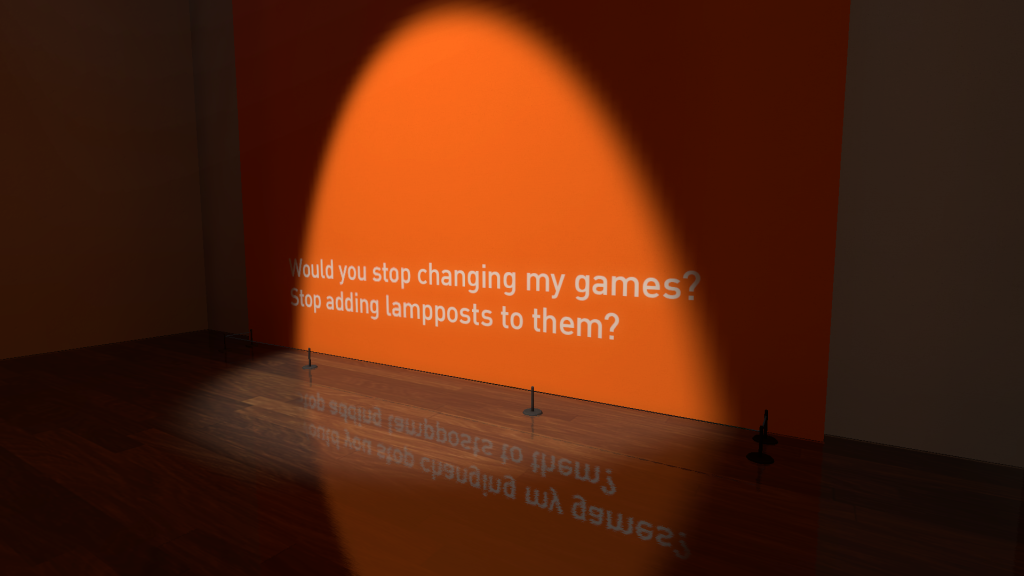

In a final twist, it is revealed that Davey altered Coda’s games for them to have an ending, so he could conclude something about them. This means that not only did Davey interpret blue curtains as depressions. No, the curtains were never blue, Davey made them blue, imagined them as such, and then argued that Coda was depressed. He wanted it to be true so bad, he created a situation in which it was so. In the case of this game the blue curtains are replaced with lampposts, and skipping puzzles, but the core of the issue remains the same.

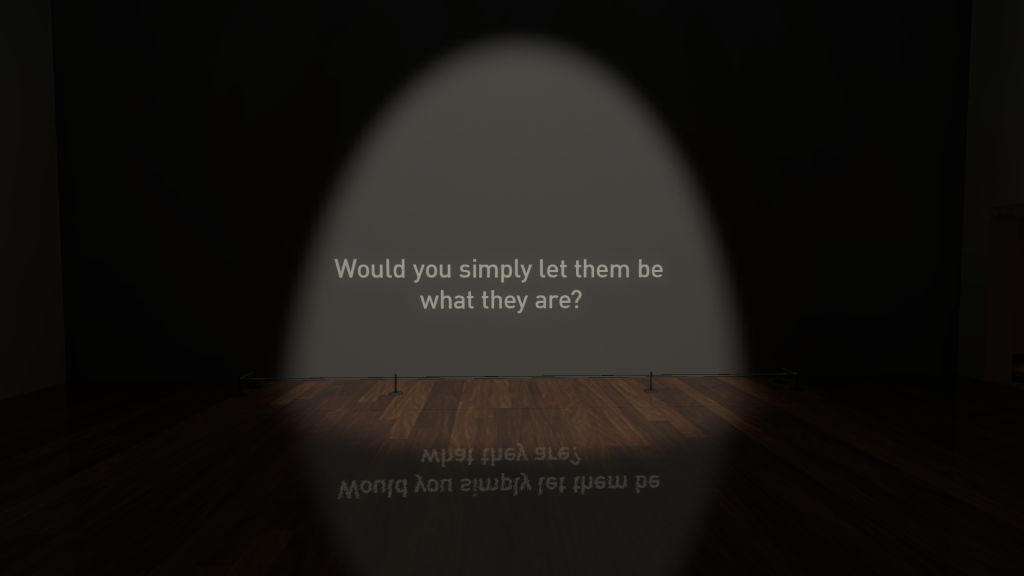

While many argue that the game is anti-critic (as seen in quotes here), this, to me, is not the point of the Beginner’s Guide. It does not judge the tension between author and audience as being wrong on one or the other side by default. What it does is explore is mistakes, and their possible consequences. How one can become obsessed with interpreting stories, and how one can claim ownership of the story of someone else. After all, where did Davey, the narrator, go wrong? It was not interpreting the games, it was interpreting the author behind them, and altering the game’s contents to reflect that interpretation. It was the obsession with finding a singular truth to the artwork, and forcefully adding that truth to the work, not the idea that the meanings of a work can be interesting, or can be discussed. The Beginner’s Guide is not anti-critic, it is at most wary of those who claim that their perspective of a work of art is the sole truth, or treat it as if it is.

This seems to be the core point the Beginner’s Guide makes about the relationship between an audience and an author. It is not the interpreting itself that is the problem. It is not just that the author’s intentions start to be lost. It is that interpretations that are not even found in the text can become more relevant than the author’s own perspective. The fear, for some authors, is the loss of ownership over a story once it is in the hands of an audience. For someone to argue that the curtains were always blue, and that it means something that, to that author, it might never have.

Banner found here. Thumbnail image found here. Game screenshots made during my playthrough.