We asked Liam McLeod to write a review of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla for us. He’s one of our beacons when it comes to medieval England, so he’s bound to have some good opinions on the game. Liam mainly discusses the landscape and the larger narrative, so no worries about (big) spoilers!

First Impressions

Things I have learnt while playing Assassin’s Creed Valhalla:

- In an open world where every cliff face is traversable, I am far too curious for my own good.

- Horses are interdimensional entities who appear upon command with terrifying reliability.

- I was not born to sail a Viking longboat.

- Oh thank goodness! Longboats have parking-assist in this game!

- Wait, are horses the Big Bad in the Assassin’s Creed franchise?

Okay, sufficed to say it has taken me a while to get my thoughts together on Valhalla. The game is expansive – vast even – and certainly meriting the credit it has received for its technological and graphical achievements. Forbes’s Dave Thier lauded the game’s “Snappy And Gorgeous” visuals, while IGN’s Brandin Tyrrel praised “Valhalla’s focus […] on the absolutely massive recreation of Dark Ages England, brought to life with stunning beauty and a level of detail I’ve rarely seen.” It is easy to grasp the sense of awe players have felt when confronted with these evocative virtual landscapes; the game’s photo mode even encourages players to get the most out of the game’s visuals:

This commitment to the game world’s beauty underscores the developers’ desire to “capture the essence of the Dark Ages” in a living world which bleeds ‘historical’ detail and authenticity.

However, leaving aside my – perfectly rational and reasonable – urge to throw Chris Wickham’s Inheritance of Rome at the next person who uses the words ‘Dark Age’ to describe this period, a modest medievalist cannot help but wonder: whose idea of ‘authenticity’ does Valhalla really service? How does it convey these apparently ‘historical’ themes? As such, this review addresses the narrative choices of the developers and the world they’ve created rather than investing too heavily in the gameplay or mechanics of Valhalla. I’ll start by addressing its visual landscape, using this as a springboard to highlight the appealing things about the title’s presentation but also some concerning aspects of the game, which ought to be addressed. The review will then go on to discuss some of the symbolism that the game readily embraces and look to place those ideas in their historical context, before getting to my overall verdict. Just to note: I’m using examples from the first ten hours of the game to try and avoid any considerable spoilers, so breathe easy if you haven’t played yet! Okay, let’s get to it.

Norway and England: Real and Imagined

Stepping into the world of Valhalla, the first thing you notice is how cold it looks. Okay, yes, I can already hear you: “a place covered in snow looks cold; very perceptive, Liam.” But really, take a moment to browse over some of the Norwegian landscape in the first few hours and the colour gradient leans so heavily into the blue spectrum that it’s almost… depressing?

The topography of the game world is harsh and stark, and while it’s stunning it is also terrifyingly off-putting. Norway in Valhalla always felt to me like somewhere I shouldn’t be, or somewhere I should flee from. There’s a beauty to its mountains and cliff edges, but there’s also something silently menacing about the place, as though it were urging you to run. Valhalla’s visual language paints the region as a land of extremes and, in many respects, it is: conflict is presented as endemic among the Norwegian tribes in this (just-about) pre-unification period. King Harald Fairhair later steps into the story to unilaterally lay claim to most of the land controlled by the different tribes and, in an almost comical display of capitulation, all the ruling elite hand over their lands with little to no fuss at all. Sigurd, the protagonist’s adoptive brother, seems to be the only one who particularly takes issue with this, but his father, King Styrbjorn, urges him to relent and hand over the proverbial keys to the kingdom because he feels that the clan’s “days of fighting are finished” and that he needs to “secure a lasting peace.”

In Styrbjorn’s defence, at this point Valhalla has done nothing but prove him entirely right. We spend much of the first few hours of the game attempting to enact a lethal blood-feud-revenge plot on the man who murdered the player character’s father in the opening scene… Well, more accurately, we try to kill him and his entire clan… All of whom are evil… Apparently. Look, things escalated, okay?

What this essentially amounts to is one of the longest and most stifling tutorials I’ve ever played in a video game. However, I think that need to escape Norway is an intentional game design choice made by the developers. You, the player, feel as your character – or at the very least Sigurd – does just before you set sail for England: you want to get out. At first, I thought this might just be the fatigue I sometimes feel when I play Assassin’s Creed games; after all they broadly use the same gameplay mechanics, user interface iconographies, and (dare I say it?) narrative directions throughout the franchise. If you picked up the controller all the way back in 2007 and successfully made your way through the crusading Levant, you can pretty much pick up the same figurative controller in 2020’s Viking Norway. After a little soul-searching, coffee, and gentle encouragement with Angus and Aris on livestream though, I began to look at the game anew. Valhalla wants you to feel a little hemmed in while you’re in Norway because it’s exactly that emotion which justifies the journey to England, for you and for your character.

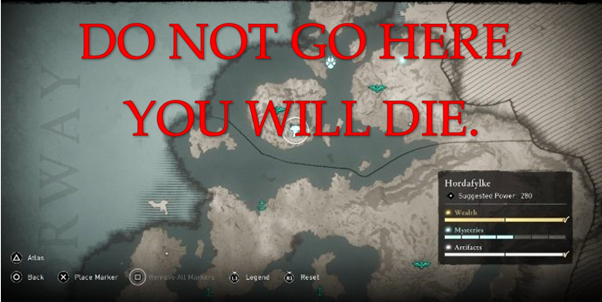

This decision is reflected as much in the map for Norway as anything else. Valhalla’s Norway has two zones and while the first one, Rygjafylke, has a recommended level of 1, the second region is Hordafylke… And Hordafylke has a recommended level of 280… Which is higher than all bar one zone in England where the bulk of the game’s content takes place. The developers might as well have stamped “DO NOT GO HERE, YOU WILL DIE” in red all over the region. (Pictured below for your convenience.)

Luckily for players [read: me] the devs thought better than to let us into there ahead of our time. It still spooked the hell out of me when I got a warning about being close to the zone border just as my longboat arrived on the shores of Harald’s little conference-to-take-over-the-world party, but thankfully I wasn’t immediately devoured by a passing Níðhöggr as a polite aperitif before its evening meal.

The point here though is that the starter zone is meant to give you that feeling of claustrophobia. The looming dread of the higher level zone that you couldn’t possibly handle, the ‘open world’ that somehow remains so uninvitingly difficult to traverse, and the desolate nature of the cold blue landscape. It has the hallmarks of what you expect from an AC game but the topography directs you away from it and ushers you forward into the rest of your adventure: England awaits.

Upon arriving in the British Isles, things already seem chirpier. Players of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey will feel right at home in these warmer, more saturated hues that evoke an almost utopic undercurrent to our landfall. The idea of utopia seems to be at the forefront of this arrival scene in fact, and the idyllic land of England initially presents itself as just as much mythological as real. The vibrant colour schemes and pastoral swathes of rural land lean heavily into the traditional idea of England’s countryside as a semi-mystical locale, home to the fae folk of Arthurian legend. One of the sailors alongside us even refers to the denizens of this new land as “green-thumbed faery folk” just to sell the idea to us even further. If we’ve just departed from a forbidding, cold, and harsh world then surely this is its antithesis. Where Norway felt almost oppressively sheer and dangerous, England feels like a love letter to one of John Keats’s poems. It’s ancient, alluring, and filled with a sense of subtle magic.

At least some of this merging of history and fantasy appears to be drawn from recent popular media. The obvious comparison here is Game of Thrones, which did a lot to return the fantasy genre to mainstream television. Like GoT, Valhalla’s fantasy elements are mostly built into the landscape for the first few hours with the only significant exception being the norns and their looms in Norway, from whom Eivor receives a prophecy. It’s an intentional slow burn; it keeps the player largely grounded in the (apparently) historical setting to establish a sense of legitimacy and realism before upending parts of that later on. In essence, it allows anyone to pick up the game and feel a sense of believability and familiarity. This desire to create landscapes which are readily recognisable even stretches into the small details, like the (somewhat-too-perfect) map we find in the war room in Ravensthorpe:

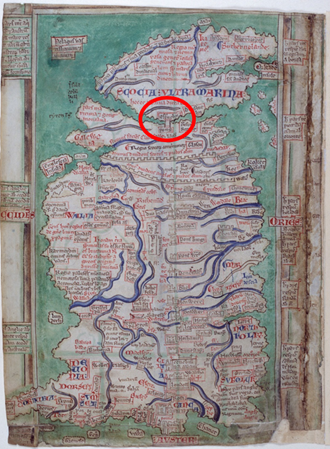

Genuine medieval maps are much messier than this neat and discrete modern looking version. They’re also usually much more heavily annotated. If we take the example of Matthew Paris’s map of Britain (c.1250), the distinction becomes clear. Paris’s map was innovative for its day, particularly his choice to orient the map northwards, but the presented landmass isn’t shown in relation to its geographical accuracy… Rather, the map was intended to be read as a guide to traversable travel plans. The water barrier between the Scottish Highlands and Lowlands, might give the impression to a modern reader of a thin strip of land connecting the two regions, but the purpose here was to indicate that the bridge at Stirling was the safest and fastest means to cross the River Forth, not that Scotland’s midlands were beset by Global Warming: The Prequel. The map created for us in Valhalla is exactly that: a map designed for us.

GoT by comparison draws elements of modern and medieval styles together in its creation of Westeros – itself inspired by the geographical and political characteristics of early medieval Britain. But where the two franchises have differed in their aesthetic minutiae, the creative direction remains the same. Build a believable fantasy; you can tear down the walls of reality with White Walkers/Viking myths later. Valhalla satisfies the demands of authenticity as defined by the public of today, not by the realities of the past.

Landscapes and Their People: Colonialism in Valhalla

The scenery in England is often so picturesque that I’d almost forgotten about my initial concerns with Valhalla’s PR courtship with toxic masculinity and white supremacy. Or at least I had done until we stepped into some of the dialogue our shipmates engage in after breaking a ludicrously large river chain which guarded our approach by boat. Presumably, King Aelfred picked up said chain at ninth-century IKEA, along with all of these ready-made Roman-Norman-blended ruins.

As we sail past this initial obstacle, Sigurd begins to tell us about England’s history. Pointing to the nearby Roman ruins we pass, he refers to England’s erstwhile rulers as “giants.” Initially, this seems almost prompted by the absurdly large triumphal arches which dot the countryside, but as Sigurd starts to tell us more about his plans for our clan, it becomes progressively clearer that he idolises these absentee architects of the British landscape and intends to build his own empire after a fashion in England, one that will not fall. The sentiment sits uncomfortably for those familiar with the imperial past of England, and the attrocities the country committed in the name of imperial progress. Sigurd building his empire is a disquieting thought. What is perhaps even more uncomfortable is how Eivor and Sigurd’s fellow Vikings readily support him: this places us, as the player behind Eivor’s eyes, in the position of enacting this imperial agenda. We become his accomplices; his active participants… We’re complicit.

Grappling with the language used here is key. When we finally see signs of life at our proposed base of operations, it becomes clear that a different kind of welcoming party is on offer than what we had planned. Rather than being populated by fellow vikings, our new home has Others walking around… “Those are not norsemen, they’re too ragged and soiled. […] They speak with twisted accents, English no doubt.” Eivor, our own character, expresses these words and suddenly everything we’ve seen up to this point takes on a darker tone. The English here are represented as lowly, brash, dirty, and this probably draws on accounts like the Chronicle of John of Wallingford, which have tended to give the impression of well-groomed vikings outcompeting the dirty natives. That Eivor describes these Englishmen as having a “twisted” kind of language perhaps further alienates them from the player: they are the villains here, in a land they ostensible own… When prefaced by Sigurd’s lauding of empire and the “giants” of ages passed, our exchange with these English soldiers as we dock our longboat takes on a worryingly colonial aesthetic. Walking across the wharf, I quickly began to feel like a European settler in the Americas, arriving to declare my manifest destiny and lay low the foul-speaking natives… In this setting, our character and Sigurd are the new “giants” in town, here to restore the glory of old as we assimilate their imperialism into our own outlooks. It’s this initial landing sequence in England which perhaps has caused most concern for me as a historian playing through Valhalla. This scene offers up the Romans as firstcomers; giants whose craft built the land and whose fingerprints can be found all over the countryside in the form of ruins. Sigurd sees something to be both admired and emulated about the precedent that Roman culture has seemingly set for England and – perhaps more significantly – for him. But what does it mean to place the Romans in this position as lauded predecessors?

Westerners tend to envision Rome (or in some cases Athens) as bearing a kind of significant primacy in the history of civilisation. The United States built its constitutional and congressional infrastructure on ideals which were often defended by allusions to – and even sometimes ouright attributed to – ancient Rome. As recently as this month, (January 2021) US Republican Senator Ben Sasse reaffirmed this notion in his speech to the US Senate after the attack on Washington D. C., directly drawing parallels between the threats to Roman democracy and American democracy. The proposition of Rome coming first is a comfortable one for westerners – particularly white, male westerners whose political agency seems, at first glance, to be enshrined in these ancient societies. Is this a fair paradigm though, and if not then what is really being elicited when Sigurd parallels Romanness with “giants”?

For fellow Classicists and medievalists, this notion of Romanitas (what it means to be ‘Roman’) is commonplace. It can be found in most of the civilisations of western Europe, even after the end of the western Empire under Romulus Augustulus in 476 CE. Imperial Britain too appealed to Roman examples when defending or exploring its self-identity, most especially in the 19th century. This significance to western culture is lost in other contexts though. White westerners don’t tend to envision ancient African or Native American populations when asked to think about ancient ‘civilisations.’ Its this underpinning cultural proclivity to value a very particular type of society and material culture which ultimately shapes the narrative that’s being presented to us in Valhalla. The early medieval English populations weren’t building empires, they weren’t even unified into a single government, and that tacitly defaults them to a lesser status in the projection of modern narratives onto historical societies. The English soldiers we encounter here are reflections of the modern biases developers (and players!) bring to history, not reflections of the contemporary identities in the Middle Ages. Colonialism looms heavy in this encounter in a video game because it continues to loom heavy in the frameworks and beliefs of western culture; Valhalla, sadly, doesn’t often do enough to challenge this.

Symbolism: Sailing Between Cultures

Okay, so that got heavy quickly. Let’s look at something more chill. Graveyards! (But mainly trees…)

Valhalla’s environmental blending of the fantastical and the historical really gives some incredible moments of environmental storytelling to the inquisitive. This shot is from Alcestre Monastery, which for most players will be their first raid of an English site in game, owing to its proximity to Ravensthorpe – our new home in the British Isles. This tree, which dominates the graveyard around Alcestre, screams Yggdrasil, particularly more modern depictions of Yggdrasil which have trended towards a more gnarled and twisting tree versus the more uniform ash trees, such as Lorenz Frølich’s 1895 Yggdrsail, which sometimes made their appearance in nineteenth-century art. As our first notable mission in England, it’s interesting that Eivor’s norse heritage would find itself interwoven here in an otherwise Christian setting: like the tree, the character stands out in the Anglo-Christian environment as an outsider in a new world.

Trees themselves were often something of a cultural divider in the early Middle Ages, and had a habit of laying claim to a certain amount of controversy. Charlemagne’s Saxon Wars (772-804) notably assaulted Germanic pagan beliefs by repeatedly insisting on the destruction of Irminsuls, trees which sat at the heart of their faith. Martin of Tours, a particularly influential saint of the early medieval hagiographical genre, found himself caught between an angry mob of pagans after trying to tear down a sacred tree; eventually they agreed to fell it… as long as he agreed to stand under it. Pagan perspectives on nature continued to inform elements of Christian belief, particularly in England, throughout the subsequent centuries and some of this influence is only now coming to light with modern scholarship that has sought to re-examine Anglo-Saxon literature in the wake of a more environmentally-minded modern world.

The littering of mythological narrative devices such as these in Valhalla is perhaps where the game shines most readily, and the developers seem quite clued into this from the moment the game begins to its conclusion. Eivor’s close call with a wolf in the opening minutes of the game really highlights this eagerness to interact with the mythological iconography of the nordic sagas. As this wolf attacks Eivor, leaving scars which result in the character’s epithet – wolf-kissed – two ravens circle overhead and eventually force our lupine assailant to retreat. The wolf is a standin for Fenrir, the son of Loki and key player in Ragnarok, while the ravens are of course Odin’s own familiars: Hugin and Munin.

Verdict:

Valhalla is, for me as a medievalist, a really complicated piece of interactive storytelling. I can’t help but appreciate the – sometimes more fantastical than fantastic – environment that Ubisoft has created for the player. It’s rich, it’s stunning, and it isn’t scared to jump face-first into the mythological symbolism of that world’s cultural context, which makes turning every corner exciting for someone who is used to reading between those lines in texts rather than video games. Valhalla’s iconographical versatility feels intentional rather than token, and that really lends the sensation that when you play the game you are in fact wandering through a considered worldscape.

Unfortunately, that’s not the whole story… While the game has certainly gripped tight to its source base and run with it, the conceptual frameworks for understanding aspects of that source base at times feel underdeveloped and carry some disconcerting connotations. I can’t help but feel that it is a particular kind of person’s idea of history: static, unflinching, choreographed and even a little intransigent at times. Valhalla is this way because it’s looking to appeal to certain kinds of audience. The game presents itself as historical, but that historicity is more often just a vehicle for reaching a mainstream clientele. Its designed to feel authentic to its community of players while still satisfying a desire for fantasy that will speak to those gamers looking for it. There are elements of history here but it’s often too crisp, too rehearsed, to have really grappled with some of the big questions of the past, and while it’s not necessarily Ubisoft’s job to educate its players, they also must be responsible for the media that they put in front of them.

History is messy. So are the people who occupied those historical spaces. That messiness isn’t a bad thing though; it’s beautiful, and worth grasping. By taking a step back and questioning the assumptions about who we think we are, history can be the gateway to a better understanding of ourselves and others. It can bridge cultures where once dogma and expectations created an impasse, and offer intellectual fluidity, versatility, and accountability where previously only monolithic narratives stood.

Valhalla’s created a beautiful longboat… I just can’t help but feel that we may have left the real Vikings back on the shore.

Liam McLeod is a doctoral researcher in the College of Arts and Law at the University of Birmingham (UK). He specialises in Carolingian saints’ lives and the reception of Jerusalem in Frankish thought and writings. When he’s not thinking about saints you will usually find him with a controller in his hands or trying to put one in someone else’s! Liam can be found on Twitter @LiamMcLeod_e