In this fourth installment of How Games Tell Tales, I will discuss how games portray unreliable narration. Using Spec Ops: The Line as an example, I will show that the hyperreality of video games influences how an unreliable story can be experienced. I will also discuss the criticism this game has of military entertainment.

Spoiler Warning: this article will spoil the most important parts of the story of Spec Ops: The Line, if you are at all interested in playing this game, then do so before reading on.

It has been some time since the last installment of my series of articles on How Games Tell Tales, sorry about that! Previously, I have discussed several ways in which video games tell stories: ideas such as Intended Play, Historical Simulation, and Hyperreality. Today, I will extend on the latter somewhat, by exploring how games uniquely portray unreliable narration. As an example of this, I will use Spec Ops: The Line. While much has been written on what unreliable narration is, the discourse lacks an insight of how games handle this type of storytelling.

Spec Ops: The Line is a war game, and one which does not shy away from showing the consequences of war, I will not include any of the more gore-related images of the game within this post, but I will describe parts of what happens. If that is something you wish to stay far away from, then this post might not be for you.

Unreliability in War

As mentioned, a lot has been written about what an unreliable narrator is. If you want to know some more about that discussion, you can click the spoiler tag below. An exact definition is not necessary for the rest of this article.

In Spec Ops: The Line, the player is in control of Captain Walker in Dubai, where he is tasked with rescuing other soldiers after an emergency message from Colonel Konrad. Unbeknownst to Walker and the player, Konrad is already dead at the start of the game. As the player enters Dubai, the game plays out like any other war shooter tends to: combat scenarios in which Walker and his allies shoot at supposed enemy soldiers.

So far, so reliable. But then, Captain Walker chooses to use a white phosphorous bomb, and it hits civilians. The player is now treated directly to the consequences of war, as they walk through a building of dead civilians. Walker opts to blame those he felt forced to shoot at, and from that point on, things start to change.

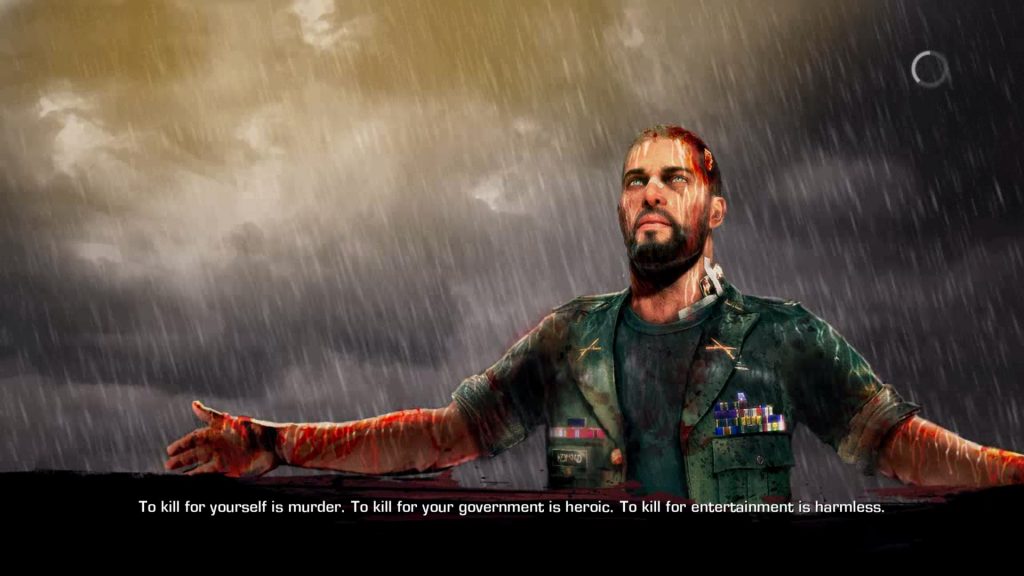

Walker finds a radio through which he talks with Konrad. He becomes angrier, and the loading screens of the game start to mockingly question the motivations of the player, asking questions such as: do you feel like a hero yet? Usually, in war games, the player is supposedly the hero, after all.

I did mention Konrad was dead, so how does Walker talk to him? The death of Konrad is revealed at the end of the game, as well as many situations being hallucinated, such as choosing which soldiers die. One of the developers suggests that Walker died in the helicopter crash, and that the rest of the game is him reliving his acts of terror in Dubai. It turns out that Konrad was not a good man, and that his regiment enforced terror on Dubai, and Walker struggles with the acceptance that he himself is a villain now as well. This struggle also extends to the player, as shown by the previously mentioned loading screens. As Walker has to confront his own evil, the player has to confront this as well: can they accept having played as someone evil?

And now that we know that Walker is unreliable, what do we, as players, do?

Choosing What To Believe

At the end of the game, the player is offered a choice. Walker confronts an imagined version of Konrad, who tells Walker that he is not the hero of this story. Konrad states that Walker only pushed on, committing atrocity upon Dubai, to try to prove that he is the good guy. And now, the player gets to choose: Shoot Konrad, shoot their own mirror image, or let Konrad shoot them.

This is where hyperreality – which we discussed before – and unreliable narration come together. It is not a question of who Walker chooses to believe, whether he wants to be a hero, and shoot Konrad, or believe Konrad, and let himself be shot/shoot his own image. No, it is a question of what the player thinks of themselves at this point. Because Walker and the player, as discussed before, are one and the same. Up until this point, the unreliability of Walker had not been revealed, and I was doing what he did. Begrudgingly so, as I disagreed with his choices. But nevertheless, I shot those bombs, I messed up Dubai’s water supply, and all those other acts of terror were controlled by me too. I chose to continue.

So what do I do? Do I believe Konrad, do I give up? Do I take control of this situation myself and choose to stop believing? Or do I aim at Konrad, do I choose to live the lie? This is a unique version of unreliable narration, one where players are not only in control of the unreliable moments, but get to choose whose version of events to believe as well.

Unreliable Militainment

A final note should be made on the fact that this is a game about war. Military entertainment is a massive part of the video game industry, and Spec Ops: The Line uses its unreliable narrative as a way to be critical of this genre.

Matthew Payne names this military entertainment “militainment” and notes that Spec Ops: The Line is explicitly critical of violence and killing in video games. Payne quotes one of the game’s developers as saying that it has become too normalised and mundane in video games to commit acts of murder. This holds especially true for war games like Call of Duty and Battlefield, in which players shoot hundreds upon hundreds of other soldiers and/or players.

While Payne notes that the loading screens of the game are critical, and the story as well – even using militainment tropes -, it should also be noted that the unreliable narrator plays right into this as well. Walker becomes unreliable because of the atrocities he commits, as he has to twist the narrative into one where he is the hero. Since other war games act like the player’s actions are heroic, Walker, as a criticism of the genre he is in, has to believe he is doing the right thing until the very end, when the player gets to judge whether games like these truly are heroic or not.

So, there we are. Spec Ops: The Line delivers a gritty story of war, in which the player controls an unreliable narrator. Whereas other shooter games will often present the player as the good guy, this game uses that to portray a protagonist who has to believe he is a hero, but has long since stopped being one. Unique to this medium, the game allows the player to choose for themselves what to believe in the story they experienced, were they a hero? Can they accept having been the villain?

If, in the future, you find yourself playing a game in which killing is mundane and normal, perhaps it is worth asking yourself: do you feel like a hero yet?

P.S. Games tell unreliable stories in a myriad of ways, such as in The Stanley Parable, or in What Remains of Edith Finch. These games were not a part of this post, mainly because I wanted to also note the topic of militainment in video games, for which Spec Ops: The Line is a perfect example.